Held Hostage

Carceral curation at the Humboldt Forum

zoé samudziThe only thing more embarrassing than the enduring presence of the anachronistic imperial ethnological museum into the twenty-first-century is an imperial ethnological museum attempting a political rebrand as though to justify its existence despite being housed in a recently rebuilt Prussian palace. Upon entering the grand lobby of the Humboldt Forum in Berlin, you—the museum-going audience—are met with a series of challenging questions on bright pink and orange banners: discursive prompts about appropriation, Eurocentrism, and taste to anticipate your experience. Translated into both English and German, the banners illustrate the nauseating institutional virtue signaling to which publics have been subjected, particularly after the global protests following the murder of George Floyd and accompanying discourses about colonial monuments. Simultaneously, they read as self-satisfied rhetorical questions, the kind that an obviously guilty person in power asks aloud in perpetuity as a substitute for even beginning to conceive of changing their behavior. Despite being an internationally renowned and world-class museum (and thus, universally accessible), the banner’s first question immediately narrows and truncates its audience: “How would you feel if your belongings were taken and displayed in a museum?” It’s a provocative question that, for many, is far from hypothetical. The global Indigenous demand for the restitution of human remains—and valuable cultural artifacts—pales in the face of the museum’s apparent need to display those objects in pleasing indexical formations behind glass display cases. The orderly museum, in other words, is a purveyor of psychic violence.

The contents of the museum, arguably, are incarcerated.

In his 1976 text Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, Brian O’Doherty describes the methodology underpinning the space as a kind of tyranny of modernism: histories and aesthetic objects are discomposed by their arrangements. He writes that “the work is isolated from everything that would detract from its own evaluation of itself,” which “gives the space a presence possessed by other spaces where conventions are preserved through the repetition of a closed system of values.” Stolen objects’ histories, too, are recontextualized by and through the civilizational and aesthetic mastery of the regimes responsible for their plunder. The surfaces of the objects are “untouched by time and its vicissitudes,” he continues, and although classificatory temporalities are imposed upon the objects, the “art exists in a kind of eternity of display” in which there functionally “is no time.” This fabrication of timescales unfolding in the vacuum of implicitly everlasting Euroamerican civilization “gives the gallery a limbolike status; one has to have died already to be there.” Someone, in fact, did die for these shimmering displays, which function almost as elegiac commemorations of eliminated—whether through settler colonial violence or deliberate absenting from contemporary discourse—Indigenous cultures and peoples.

In describing the museum as a “secular temple,” art historian Zach Whitworth notes that the “halting of time is a magic that manifests not from the mystique of the museum itself but its temple-derived aspects, thus this power is wielded by other institutions stemming from that same ancestry.” The development of the museum is coterminous with that of the prison, as British sociologist and cultural historian Tony Bennett famously noted in his critique of the “exhibitionary complex.” Carceral time-space is a strategic spatial organization of manipulable temporalities imposed upon imprisoned docile bodies as a means to order (control of the prison space), punish (the duration of the punitive sentence of imprisonment), and torture (the psychic cruelty of solitary confinement). We might describe the maddeningly artificial imperial temporality in which order and meaning are born out of the twinned colonization and disappearance of Indigenous peoples and lifeworlds and the strengthening of the conquering civilizations as social death. The contents of the museum, arguably, are incarcerated.

This process of absenting in the physical world is made manifest by the museum’s collection, which in turn reflects the imperial logics that govern the institution. From the curatorial decisions that arrange the pieces inside of the ethnological space to the architectural history of the building that houses the collections, the Humboldt Forum’s entire being as a cultural-educational institution is shaped by imperiality—an episteme that shores up the institution’s resilience even while calls to dismantle it (or, at the very least, to return many of the objects and artifacts trapped within its walls) are growing louder and louder.

*

But as with all ethnological museums, the Humboldt Forum is a monument, ein Denkmal: an erected representation of an event or phenomenon, a preservation of significance, a noteworthy place within a broader culture of German remembrance

From the lobby at floor zero, you climb two never-ending escalators to the collections on the second floor. Entering into the African collection, part of the Ethnological Museum of the State Museums of Berlin, you’re confronted by an aesthetic and political eyesore. Enmeshed in calls to decolonize museums—political theorist Ariella Aïsha Azoulay reasonably holds the impossibility of this feat—are questions about the target audience of this colonialism-critical yet altogether colonial institution that seem formally answered by the insipid banners in the lobby downstairs. But as with all ethnological museums, the Humboldt Forum is a monument, ein Denkmal: an erected representation of an event or phenomenon, a preservation of significance, a noteworthy place within a broader culture of German remembrance.

American-style social justice profiteering, à la Robin DiAngelo, even makes an appearance—“I have a white frame of reference and a white worldview”—in the attempted rebrand, in a country that is notoriously reluctant to robustly acknowledge its colonial complicity. The statement was a swaddle for museumgoers, a preemptive warning anticipating the inevitable discomfort and confrontation, but still breathtakingly shallow considering the fairly straightforward engagement of genocide that would follow less than a hundred feet away. I had the misfortunate of entering the museum along with a small group and without my headphones, which I had accidentally left at coat check. I heard the guide prompt the group for answers to DiAngelo’s provocation: one white woman clumsily but confidently described the problematics of Eurocentrism, clearly proud of her knowledge. There weren’t right or wrong answers in that space of learning, the guide reassured, but her approving tone indicated that one was certainly correct.

The White Fragility author’s words were emblazoned on an interactive scaffolding structure whose words and images preface the collections with a heterodox approach for evaluating stolen-kept objects. They should be understood within the context of imperial plunder, “collection” is a euphemism for theft, and so on. This was almost an impressive point of introspection, if not for the fact that the massive building is still filled, by its own admission, with stolen things. In the end, I reckon I was more uncomfortable than the guide warned the white visitors they may be, but “uncomfortable,” here, is a self-protective adjective for existentially harmed, spiritually unsettled, completely devastated in the face of the transnational kleptocratic enterprise that is ethnological museology. Among the solemn adult workers and caretakers, a group of schoolchildren with notebooks stood in front of the glass cabinets filled with African ephemera. This was hardly my first confrontation with this violence, but nevertheless, I ashamedly felt myself starting to hyperventilate. Next to an exterior window and facing away from the center displays, I found a quiet and sufficiently dignified place to cry but I still could not escape the curious gazes of a number of passing patrons who slowed and glanced back at me multiply as though attempting to translate my stifled sobs.

I am not an Indigenous person, rather a diasporan just one generation removed from the degradations and humiliations of British colonization in what is now called Zimbabwe. But in that room, and particularly in that moment of emotional arrest and vulnerability, I shared something terrifying with the artifacts stolen from Cameroon, the present-day Democratic Republic and Republic of Congo, Togo, Namibia, and elsewhere. What overwhelmed me was a deep metaphysical affinity with these artifacts (some of which were direct representations of place-specific ancestors): a keen recognition that I was inserted into a staged tableau of subjection that transformed evidence of plunder into a demonstration of civilizational might and epistemological domination, a studied but still indescribable horror at the persistence of the perversities of imperial memory. My mind flashed to the history of the Great Zimbabwe birds, eight soapstone carvings of the now-national bird that decorated the ruins of Great Zimbabwe, one of which was stolen in the late nineteenth century by German explorer Willi Posselt who deliberately trespassed on sacred ground and sold the sculpture to Cecil Rhodes. Other birds were stolen during subsequent European archaeological expeditions, another of which was circulated among German ethnological institutions, and finally returned to Zimbabwe on permanent loan by the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation in 2000. This kind of permanent loan, a lending that refuses to cede sovereign claim, is a permanent debt; and this debt of emancipation, per Saidiya Hartman, is situated at “the center of a moral economy of submission and servitude and was instrumental in the production of peonage.”

Cambodian choreographer Sophiline Cheam Shapiro recently penned an article about being forcibly removed from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York for dancing a ritual prayer in front of statues of deities, including the god Harihara, that had been looted from Cambodian temples and brought to New York City through international circuitries of illicit trade. Her performance of the appropriate interactions between the statues and their cultural contexts mirrored the recurring anguish felt when I return, again and again, to these spaces that contain cultural materialities from which we as Africans have been forcibly untethered. Unlike the stolen artifacts, I would board a plane and return to a home mostly of my choosing. But like the objects, I’m also a conscript of antiblack empire. Following Fred Moten’s explication of the Black moan as a “complex, dissonant, polyphonic affectivity of the ghost” that reverberates through and beyond a visual rendering of antiblack abjection, the objects’ wordless, dirgeful moans were unbearable: the collective choruses of their intoned out-of-placeness were earsplitting. I grieved and wept because I became acutely aware of how deadened I felt, too.

DiAngelo’s inclusion as a conceptual frame for the violent materialities of imperial epistemicide is a fittingly regressive decision for Germany—a country that not only struggles to acknowledge its imperial past, but also generally struggles to talk about race, as the word for it (Rasse) is associated with and attributed to Nazism. The national guilt complex inherent to Holocaust exceptionalism also determines narrations of Germany’s historiographic trajectory, as Germany’s race crafting extended into its African colonies and the genocides and massacres it perpetrated decades before the Second World War: the brutal suppression of the Maji Maji uprising in German East Africa (mainland Tanzania, though the colonial territory also included Burundi and Rwanda) and the attempted elimination of the Ovaherero and Nama (and Damara and San) peoples in German South West Africa (present-day Namibia) are just two such examples that occurred almost simultaneously on opposite sides of the continent. The very scientific and anthropological apparatuses that drove the hierarchical codification of global peoples also animated the methodical theft, collection, and profitable museal trade of said people’s cultural artifacts. Interestingly, the Humboldt Forum’s curation follows the same organization and management of pre-Nazi racial classifications. Historically, “culture,” along with “civilization,” carried an anthropological connotation of and made reference to the dichotomization of Kulturevölker (civilized peoples) and Naturevölker (primitive peoples), in which the former—Europeans—were cast as peoples capable of development and the latter—here, Black Africans—were peoples without a history (or a future). Culture is synonymous with civilization and race; so cultural designations, too, function as global assignations of practice-as-sociocultural (i.e., racial) determinants.

Next to an exterior window and facing away from the center displays, I found a quiet and sufficiently dignified place to cry.

Responding patiently to a question asked by a student among a group of schoolchildren, the guide explained that the cabinets holding African art and artifacts were dimly lit because they “could not receive sunlight and had to be protected.” Despite recognizing that conservation practices demand carefully maintained atmospheric conditions, this comment, which excised storage from the conditions of theft the guide had previously mentioned, was darkly amusing, though inadvertently so. It was ironic that objects from heliophilic equatorial African countries were now so vulnerable to light that they were kept in darkened display and storage spaces. But it was even more telling to see how this logic was spatialized throughout the museum. Organized by landmass geographies, the darkened African hall is near to an Asian hall: a brightly illuminated room adorned with continental Asian (read: East Asian) instruments and a celebration of “sounds of the world.” But the adjacent hall of Oceanic peoples is, once again, a dimly lit room housing classic ethnological wares: clothing and adornments worn by mostly denuded peoples, canoes and hunting equipment, and, of course, masks. Even within a racist museal enterprise, a chromophobic lighting system reinforces the presentation of dark African and Pasifika peoples as Naturevölker and the recognized musicality of “Asian” civilizations as Kulturevölker. Sensitive nonusage of Nazi-linked Rasse notwithstanding, Germany fittingly opted for classic imperial racism.

*

I heard the guide prompt the group for answers to DiAngelo’s provocation: one white woman clumsily but confidently described the problematics of Eurocentrism, clearly proud of her knowledge.

Although Germany’s formal conquest in Africa was far shorter than the invasions by Europe’s other imperial powers (from the 1884 Berlin Conference until Germany’s defeat in World War I), a quiet celebration of its imperiality rests in the country’s investment in Prussian history and architecture, including the 2013 reconstruction of the Berlin Palace, which now holds the ethnological museum. The Humboldt Forum’s creation—it opened to the public in July 2021 during the ongoing pandemic—is an egregious materialization of German imperium sine fine. Though the notion of “empire without an end” was Virgil’s poetization of the boundlessness of the Roman empire, the recreation of the Berlin Palace was a tasteless twenty-first-century celebration of Prussian imperialism. From 1451 to 1918, the palace was the residency of the House of Hohenzollern, the dynasty whose members comprised the kingdoms of Prussia and Romania, the Margraviate of Brandenburg, and the German Empire. An astounding exemplar of Baroque architecture, the palace was badly damaged during Allied bombings of Berlin in February 1945. Located in what would become the German Democratic Republic following the postwar bifurcation of Berlin, the palace was demolished in September 1950. Part of its site became incorporated into the East German state council building in 1964, and then, from 1976, the site was entirely subsumed by the modernist Palast der Republik, the East German parliamentary building and multiuse cultural structure, which was inhabited by the legislature until reunification and dissolution of the parliament in 1990.

Closed to the public due to asbestos contamination, the building was reopened to visitors in 2003. But in 2003, the Bundestag—previously the parliament of West Germany—demolished the Palast der Republik, to the chagrin of the German public, particularly former East Germans who understood the demolition as the destruction of the city’s culture and the former republic’s history. With the €677 million reconstruction of the Berlin Palace underway in 2013 (this converted to around US$824 million at the time of its completion in 2020), a crucial material iteration of imperial historiography was complete. Along with its plundered treasure, the palace-cum-museum concretized a seamless historical revisionist trajectory from Prussia to West Germany to a reunified German republic sutured through the effacement of East German space. The institution celebrates a Heimat (which translates approximately to “homeland,” though it broadly encompasses German society, culture, and statehood) and a quietly accessible patriotism as historical commemoration otherwise negated by the deep abiding shame of Nazism at the nucleus of the country’s national identity.

Animated by a romantic nationalist impulse to expand beyond the territory of its metropole, Germany was a relatively late entry to the continental rush to establish colonies in Africa. Hosting the Berlin Congress of 1884–1885, which methodically carved and apportioned the continent among Europe’s great powers, Germany was given colonies in present-day Namibia, Cameroon, Togo, and Tanzania—nation-states representing significant proportions of the Humboldt Forum’s African holdings. While many items in the collections of ethnological museums across Europe were acquired through imperial missions in those respective countries, many others, still, were accessed through illicit exchange throughout the Western world. The Benin Bronzes, the thousands of metal sculptures stolen from the Kingdom of Benin (in the present-day Edo State of Nigeria) following a punitive British expedition in 1897 that brought down the African empire, are particularly prominent symbols of this profitable expropriation and discursive centerpieces in long, ongoing restitution debates. The continuous violence of plunder and knowledge production through this historical revision within the museum is described by archaeologist Dan Hicks as “necrology,” and the epistemicidal underwriting of African history as “necrography.”

Unsurprisingly, these precious bronzes form the nucleus of the Humboldt Forum, as in many other institutions. They are held in their own room, separated from the other African artifacts, displayed both in traditional glass-boxed plinths and a bleacher-like centerpiece that allow them to be circled and scrutinized and appreciated from all angles. It is as much a spectacular presentation of cultural pride (where, again, coloniality constitutes German culture) in their possession as public edification and learning. As with the nonsensical banners prefacing thousands of square meters of dubiously acquired artifacts, there is an informational display in this room that describes the necessity of ongoing restitution efforts—the need to send the sculptural pieces back to the places from where they were taken, though this waffling and performed commitment has been deliberately unpunctual.

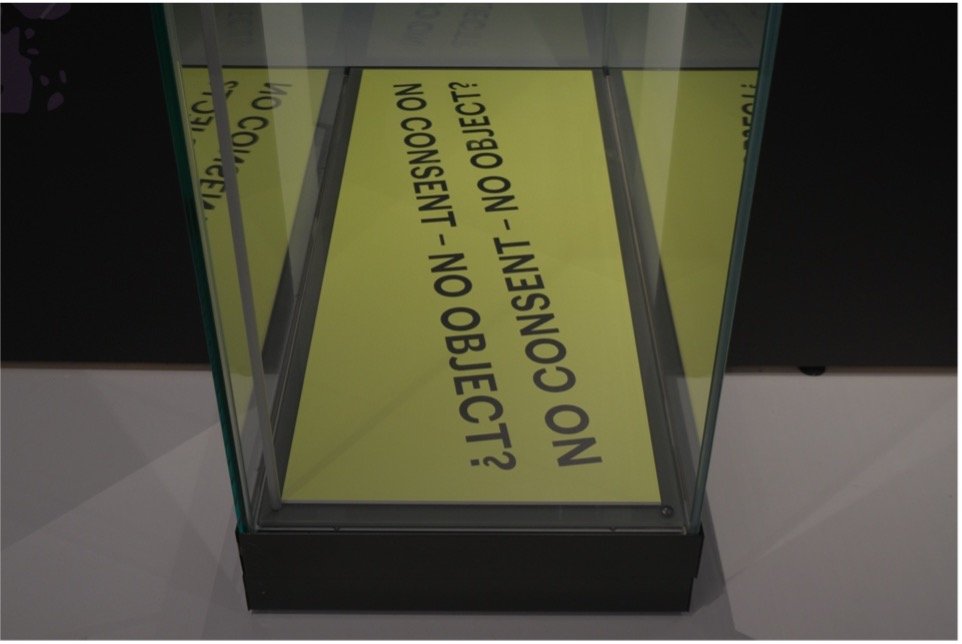

Not far from the bronzes is the floor’s conclusion—the collections are organized around a squared courtyard. A mirrored, empty case that reads “no consent—no object?” punctuates the show along with the colorful banners. It suggests a discomfiting absence of ethics to the museological endeavor. The suggestion that a lack of consent would transform imperial collection practices is navel-gazing institutional introspection that grossly misdescribes acquisition and the decades Africans have spent insisting on the return of their artifacts. In fact, Bénédicte Savoy, French art historian and co-author of the 2018 landmark report on the status of African art in French collections, resigned from the advisory board of the Humboldt Forum because of her displeasure with the museum’s handling of artifacts from the former German colonies.

Despite the museum’s insistence on positioning itself as a different kind of ethnological museum, it is, like all the others, simply a repository of what scholar Fazil Moradi describes as catastrophic art: art that “retains and speaks about and beyond the precolonial and colonial systems of knowledge and life forms . . . and is held hostage by, colonial epistemicide as tied to social and political murder.” Considering the capture of repatriation discourses by the statist (and state power–reinforcing) processes of establishing provenance and exchange between governments, Moradi describes how this art presents a radical disturbance to the Westphalian system further codified by these ethnological museums. The museum’s curation of colonialism asserts that Africa is represented by no longer existent kingdoms and territories, and the Prussian Empire—via its continuities in Germany’s nostalgic statecraft and the political aesthetics of the Humboldt Forum—contains and holds lawful ownership over art from außereuropäische Kulturen (non-European cultures). This is incompatible with a conception of hospitality that demands an address of this epistemicide. This irreparable violence cannot be resolved by the state’s reluctant and now-obligatory politics of recognition, but by an ending of the imperial world and its regime of property.