Within a Barren Grove

Repression, adolescence, and the modern therapeutic boarding school

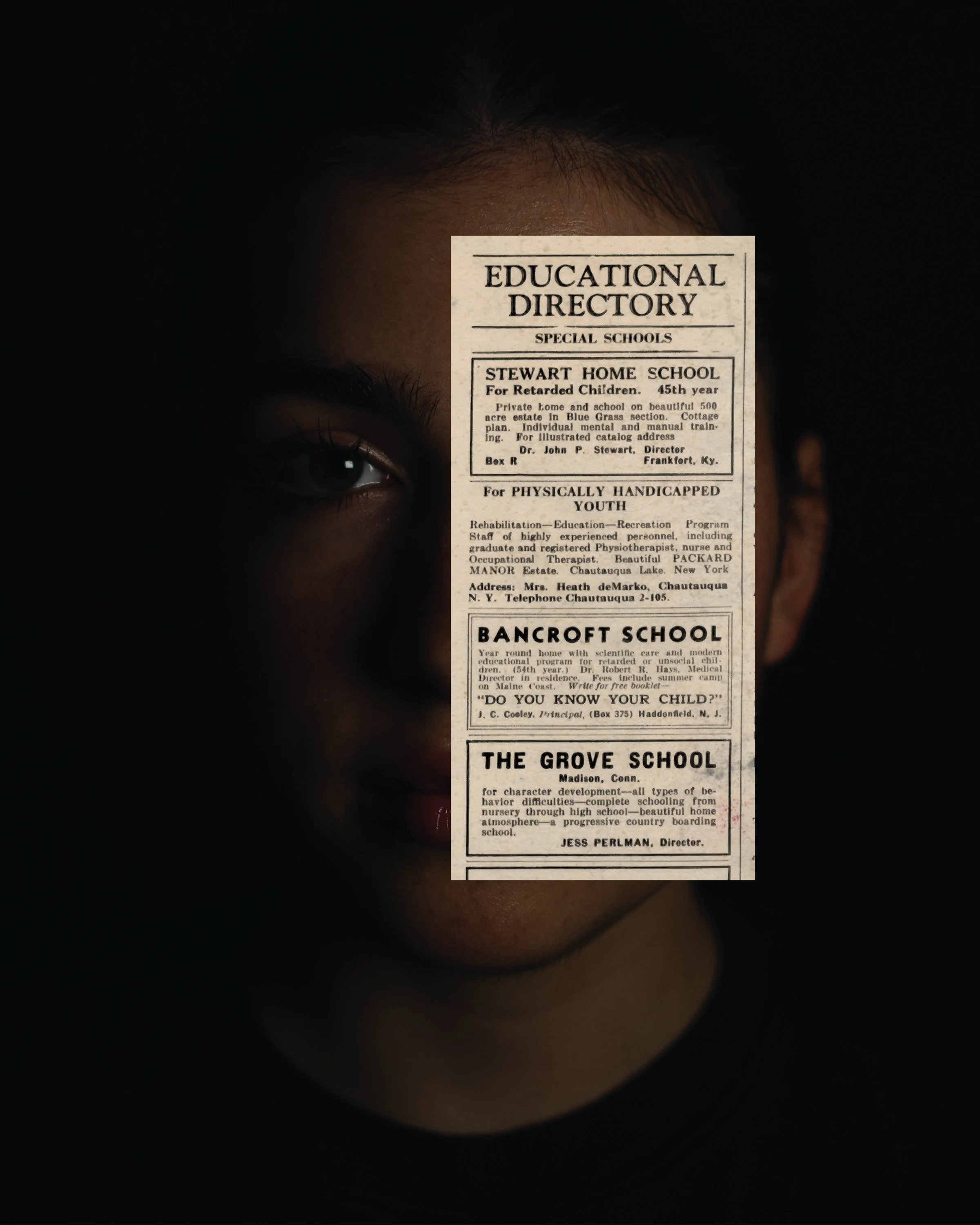

Wendy LottermanAn advertisement in The Rotarian from 1937 describes The Grove School, a therapeutic boarding school in southern Connecticut, as a place “for character development—all types of behavior difficulties—complete schooling from nursery through high school—beautiful home atmosphere—a progressive country boarding school.” Appearing beneath two ads targeting the families of “retarded children” and one for the “physically handicapped,” the ad for Grove stands out. Its emphasis on character development and the capaciousness of “behavioral difficulties” shifts away from taxonomies of non-normativity toward a more open understanding of psychic distress. Diagnostic types, like those listed above the Grove ad, attempt to describe the individual outside a context of dynamic cause. “Difficulty” names something relational—the friction of moving parts indexed by the experience of a subject.

Jess Perlman, the ad’s author, was a philanthropist, educator, and poet with a background in service work. Immediately after receiving his law degree at CUNY in 1915, Perlman became the director of Irene Kaufmann Settlement in Pittsburgh, where poor Jewish immigrants found access to a network of social services upon arriving in the US. Like other settlement houses, the institution was double-edged: although it materially cushioned the landing of under-resourced immigrants upon their arrival in the New World, it also sought to groom its members into effective American wage laborers who could provide for themselves, and thus no longer rely upon social services. Elements of the settlement house are reproduced in the structure of the therapeutic boarding school: both pair resource consolidation with intensive, short-term residence. Service workers found lodging in the settlement house, just as Grove’s crop of teachers live on campus and double as “dorm staff” who provide emotional and social support beyond the classroom.

But if Perlman attempted to build a network of care to uplift struggling minors, that is not what Grove eventually became. The school’s transformation during the late 1980s into a for-profit corporation whose solvency depends on the continuity of consumer pathology is far from its roots in philanthropic—if normative—service work. This can be explained in part through institutional proximity to other forms of privatized care, like rehab, but there is something more pernicious in the custodial life of this institution. While Grove’s capacity to substitute for secondary school provides a reasonable alibi for its primarily adolescent population, the actual management of this demographic is not strictly curricular. Impressionable, pubescent students—who have been separated not only from family, but from the world—provide the “school” with a dangerously receptive target for psychic, social, and sexual norms whose enforcement is entirely unregulated.

As yet, no federal agency exists to oversee such institutions, and states like Utah, which are home to many, only recently began introducing legislature to protect children. Like other private schools, the therapeutic boarding school (TBS) is free to operate under the banner of its own ideology; consumers who are unhappy with the product are free to simply discontinue. But despite the sordid histories of abuse attached to these institutions—some of which were recently exposed by Paris Hilton in a 2020 documentary—parents are often left with few other options after inpatient care has disrupted a child’s ability to keep up with public education.[1] Many who arrive at the TBS have already spent months cycling through bouts of hospitalization, various forms of special education, and wilderness programs. And, despite the ostensible freedom to discontinue, these schools rarely recommend that students leave.

*

The Grove School exists in a claustrophobic double negation of privacy and the public—a wooded sliver of surveillance nestled on backroads in a wealthy Connecticut shore town. Freedom of movement comes in degrees. Campus security is addressed to the highest level of possible risk, meaning that the student body of motley pathology is managed according to the liability of a runaway. To protect against this flight risk, Grove places each new arrival under “supervision.” Students remain within eyeshot of a staff member until good behavior earns the right to stray for fifteen minutes at a time. After “15s,” one is eligible for “30s” and so on, until “hours” can be exchanged for “downtowns.” When I was at Grove between 2004–2006, this highest tier of freedom was limited to one-hour, making a two-mile round trip “downtown” nearly impossible. The school’s location at the end of “Copse” road—a literal synonym for “grove”—limited my options to a strip mall where CVS was the only business I patronized.

If the highest level of freedom at Grove was a rushed commute to the pharmacy, a similar constraint was placed on the psychic distance that I could safely travel. When I attended Grove, phones were available for rare and supervised use, and access to the internet was limited to a few highly monitored computers. Not only was the world hard to reach, but the promise of returning to it was contingent upon adherence to ideologies of hygiene, health, and sexual normativity. As an example, my own adolescence was highly pathologized, despite progressing along familiar lines of fear and desire. My on-campus therapist at the time did not hide the fact that her daughter was a minor celebrity after writing and directing the bisexual classic Kissing Jessica Stein (2001). Wrongly presuming that she’d be open to the vagaries of desire, I confided something that I cannot entirely remember—something about wanting to be a boy. This confession, whatever its content, was treated like a key to the riddle of my barely delayed puberty and triggered a series of strange events: my parents were brought in for a meeting that breached confidentiality, I was taken to specialists to test my bone density, and a pediatric pulmonologist asked me to undress under the guise of an asthma check. I never understood the purpose of that request but suspected that something in my chart made her curious about my sexual develop- ment. There was concern amongst my team that I’d convinced my body out of menstruation due to not wanting it badly enough, and that this lack of demonstrable femininity was a sign of danger inflicted by my mind upon my body. I was encouraged to perform femininity to promote better physical health. Rather than coax me toward healthy development, this specious conspiracy occupied my mind at all hours of the day and convinced me that certain thoughts would cause lasting physical damage. So, while acts of sex and sexuality were highly policed and met with punishment, androgyny was also a psychopathology.

In retrospect, I partly attribute my slight and ambiguous appearance to a lack of adequate food and the total forfeiture of my body to a randomly assigned psychiatrist. In records that I recently requested, I learned that my non-psychotic adolescent depression was treated with mood stabilizers, anticon vulsants, anti-anxiety drugs, and antipsychotics all at the same time. At age 15 my regimen was the following:

Lithium, 150 mg 8 .a.m. & 300 mg 9 p.m.

Depakote, 125 mg 8 a.m. & 125 mg 9 p.m.

Buspar, 10 mg 8 a.m. & 15 mg 5 p.m.

Seroquel, 25 mg 9 p.m.

Lamictal, 62.5 mg 9 p.m.

Synthroid, 50 mg (odd days) 8 a.m.

Synthroid, 75 mg (even days) 8 a.m.

Singulair, 10 mg 9 p.m.[2]

This was one of the school’s most effective measures of security and containment—the pervasive use of antipsychotics as a tool for enforcing docility and an unnaturally early bedtime. While medicating minors involves a complicated and imperfect calculus of risk management and consent, and some students may have legitimately required heavy doses of serious drugs, my particular “cocktail” made it impossible to report on the effects of any single medication. The already challenging task of psychic narration—demanded in therapy, group therapy, psychiatry sessions, dorm meetings—was compounded by a frequently revised diagnosis and the fog of so many chemicals. I remember telling my psychiatrist that I couldn’t sleep because I was so anxious about my parents running out of money and being subsequently prescribed 25 milligrams of Seroquel. When I attended Grove, yearly tuition was $73,000, a figure that students threw out when the dorms grew mold or the food was particularly bad.[3] I was told much later that though most families paid out of pocket, my mother had convinced the state of New York to cover my tuition. The school’s dependence on private financing combined with what I remember to be reluctance to recommend discharge, produced a paradox wherein parents were investing in their child’s ability to return to the world while ironically ensuring the opposite.

The securitized campus and its epistemic correlative are justified on the basis of a volatile population. In many ways no institution can be blamed for the failure of such an ambitious project; the mix of delinquency, intellectual disability, and suicidality creates a sludge of unmeetable needs, even without the addition of a curriculum. But in many cases the school’s restrictions and recommendations exceed the remit of safety, and spill into repression. The withdrawal of psychic freedom conspires with preexisting struggles to produce a campus full of maladapted adolescents who have not only fallen out of sync with curricula, but with life itself. Thoughts of money, sex, and escape are managed by drugs and punishment. And the “difficulty” that Perlman ostensibly sought to lessen is secured by the cauterization of social life at a time when relations—social, sexual, familial—are meant to crucially develop.

“The withdrawal of psychic freedom conspires with preexisting struggles to produce a campus full of maladapted adolescents who have not only fallen out of sync with curricula, but with life itself.”

*

The origin of the modern therapeutic boarding school is often located in a now defunct drug rehabilitation center in Santa Monica called Synanon with an extant offshoot in Germany.[4] The center claimed record high numbers of recovery among its participants who engaged in a hostile form of group work called “attack therapy,” conducted under the rubric of truth-telling. In The Elissas (2023), a non-fiction portrayal of female adolescence and the Troubled Teen Industry (TTI), Samantha Leach describes the legacy of attack therapy at therapeutic boarding schools. “In 1967, former Synanon member Mel Wasserman founded CEDU, the first-ever therapeutic boarding school, molded in Synanon’s image, from the use of attack therapy to founder Chuck Dederich’s withholding of members’ rights.” Spring Ridge Academy, an Arizona-based therapeutic boarding school where Leach’s best friend began her descent into the TTI, carried the torch of attack therapy. Rebranded as “feedback groups,” this practice invited students to claw at the perceived insecurities of their peers, often beginning with superficial insults, then digging deeper into character flaws.

Before it closed its doors in 1991 after more than thirty years, Synanon would come to be perceived as a particularly vicious cult. While some of the center’s rules were more visible than others, such as compulsory head shaving—a feature that gained visibility when several prominent LA directors cast members as extras in dystopian films—there were also forced sterilizations, vasectomies, and abortions. Yet, even though Dederich saw children to be a waste and likened abortions to popping a pimple, the campus was also home to a “hatchery” where the children of members were collectively raised. Such a service is demonstrative of Synanon’s most consequential tenet: that none of its members could leave. After structuring the program around 2-year stays, Dederich understood that the only way to truly eliminate recidivism was to keep recovered addicts from ever reentering the world.

While Synanon may share its emotionally caustic approach with several therapeutic boarding schools, Perlman’s career provides an occasion to consider another precursor. The first settlement houses emerged in the UK at the turn of the 20th century as a way of creating generative pockets of wealth and welfare in poor urban areas. Workers volunteered to live in collective domiciles where knowledge and culture could be spread among their under-resourced neighbors. In such settings, the biological family gave way to other forms of communal living in which same-sex relationships among social workers were not uncommon. While social reform and ideologies of hygiene were in place, these spaces were primarily addressed to conditions of economic crisis and sought to lift members out of poverty through mutual aid.

This framework took on a slightly different flavor in the United States, particularly in the early 20th century, as waves of immigration brought poor affinity groups from Europe to the American East Coast. American settlement houses, like Irene Kaufmann (IKS), were thus populated by immigrant-dominant urban communities who took shelter in their subsidized residences and were educated in the social values of a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant lifestyle. Jewish settlement houses lacked this final aspect, but were equally designed to prepare residents for gainful employment and class ascendancy through an education in labor and culture. In the US, settlement houses were often funded by Jewish philanthropists, like Irene’s father Henry Kaufmann, a proprietor of Pittsburgh’s largest department store.

A 1926 report from the Bowling Green Neighborhood Association in New York City states that they never prod immigrants into citizenship, “but when they have reached the point where they want to become citizens, we give them all the help we can with their papers.” In the early 20th century, citizenship was a path toward stable employment, an express goal of these programs. While I suspect that the ideological apparatus of the settlement house and its offshoots was not entirely free of conditioning and coercion, there is something tragically unfamiliar in this proclamation of deference to the will of its members.

If the settlement house existed to prepare its residents for the world, albeit a world steeped in racial capitalism, the contemporary therapeutic boarding school exists to separate its residents from the world, making it less and less possible to return. In addition to pushing medication and enforcing limits to physical movement, the school typically establishes a monopoly on narrative authority, making it impossible to author a reliable desire to leave. As Leach observes:

Communication is often restricted at therapeutic boarding schools. In some, there may be a staffer listening in on the line. When students write letters home, the staff often reads them ahead of time, sometimes crossing out any salacious lines or throwing them away altogether. And if a student is somehow able to get through to their parents the truth of their experience, the staff might play their trump card: reminding families that this is the kind of lying and manipulation they sent their kids away for in the first place.

This squares with my experience of trying to leave, and the resistance from the care team who recommended against it. The only elective exit I witnessed was that of a classmate who burst into the nurse’s office—where I wiped down counters for $5 a day—with shaved eyebrows, screaming, before I watched him slam the door and jump from the roof above us. When someone on the outside tried to add his suicide to Grove’s Wikipedia page, an unknown editor with links to Connecticut repeatedly removed it.

“The only elective exit I witnessed was that of a classmate who burst into the nurse’s office—where I wiped down counters for $5 a day—with shaved eyebrows, screaming, before I watched him slam the door and jump from the roof above us.”

*

In 1956, Jess Perlman sold the Grove School to Jack Sanford Davis, a former United States Naval Researcher with a PhD in psychology, and his wife Helen. While Jack and Helen steered the school for 30 years, they undertook other local business ventures including a real estate firm that sought to gentrify Madison’s downtown. Jack also sat on the town’s board of finance for 20 years, encouraging the purchase of beachfront land that would become Madison’s exclusive Surf Club.

On Yelp, user “Fp C.” describes his time at Grove toward the end of Davis’s reign as “a bewildering, alienating and unnecessarily negative experience.” He continues: “I often wondered how I went through those hellish eight months without more scarring, or whether I hadn’t yet uncovered my trauma. Owner Jack Davis was indeed a peculiar, transparent huckster.” Among Davis’s huckster peculiarities is the discrepancy between his ventures. Until recently, Grove’s schoolhouses were apparently repurposed chicken coops and horse stables, while the Surf Club offers 45 acres of manicured beachfront. Fp C.’s post, which remains beyond corroboration, continues to inject lurid details into the scene of his de tention:

It was a sad vortex of suffering and dysfunction. One example: Grove imported over-qualified teachers from the Philippines and paid them $2000 [not a typo!] a year. (Theoretically they were receiving $8k more in grad school tuition, plus the squalid room and board we all enjoyed at Grove.) The Filipinos (often Masters or Ph.D.’s in their home country) needed their job to legally be in the US, so they were bound to Jack Davis like indentured servants for their job/education/visa and meager stipend. [sic]

Another user echoes this portrait of Davis, adding that students were disciplined by threat of transfer to a psychiatric hospital, and staff were disciplined with the threat of revoking their draft exemption from the war in Vietnam.

Despite Davis’s dark, proprietary spirit, Grove only became the for-profit corporation that it is today when it was purchased by Richard Chorney. In his capacity as CEO, Chorney eventually appointed his son Peter to Grove’s corporate board and handed him the role of executive director. My two years at Grove were during this period, when the school held tight to its consumer base and therapeutic recommendations were inextricable from corporate strategy.

When I returned to Grove several years ago, I flipped through a yearbook with my former advisor who gave me updates as I pointed to peers. As I remember, many of my classmates had died. The beguiling repetition of this awful fate is part of what led Leach to write The Elissas, a story of three girls with the same name spelled differently who met at Ponca Pines Academy and all passed away within a decade of leaving. On the surface, Chuck Dederich’s suspicion was cruelly correct: the only fail-safe way to prevent relapse is to keep people from leaving rehab. And the only way to prevent graduates of the TBS from failing on the outside is to keep them forever on the inside.

But Synanon’s members were all addicts before joining the program, whereas Grove’s students were not necessarily in need of detention. The TBS is, after all, a school. It is an expensive, last-ditch opportunity for minors to complete their education after falling out of step with the unrelenting pace of a public or private school curriculum. While most students were referred by outpatient psychiatrists or their parents, the school had a contract with the Department of Child and Family Services Family Services between 2010 and 2015.[5] This means that some students were not sent to Grove for their own pathology or misdeeds, but as a result of family policing.

*

Reckless capitalism and the apparent mismanagement of minors leaves little to admire in either Chorney or Sanford. Perhaps this is why I find myself reviewing the details of Perlman’s career with sympathy for the things he got wrong. Among other peculiarities of his life, I’m pleased to discover that Perlman was also a poet who published several now out-of-print collections.

In the absence of access to his four books of poetry—one titled Looking-Glasses (1967) and another This World, This Looking-Glass, and Other Poems (1970)—I’m left only with the apparent fascination that he took in the mirror. But rather than reach immediately for Lacan, I want to consider Virginia Woolf’s 1929 story “The Lady in the Looking Glass” to think more seriously about foreclosures of narrative access, which structured my two years at Grove.

Woolf’s story is very simply about narration, or the attempt to put someone else into language. Its narrator is circumspect and dissolved by the anonymous pronoun “one,” while Isabella, the object of observation, is shadowy and enigmatic. “It was strange that after knowing her all these years one could not say what the truth about Isabella was.” Her surroundings are similarly encrypted: “Under the stress of thinking about Isabella, her room became more shadowy and symbolic.” But the climactic event of the story does not involve Isabella at all. Suddenly, a “large black form loom[s] in the looking glass,” and drops a pile of imprecise objects. Struggling to translate any of the reflected forms into language, the narrator describes the scene as “unrecognizable and irrational and entirely out of focus.” Slowly, the ambiguous scenography relents to shapes. The looming figure is the postman, and the deposited objects are letters delivered for Isabella.

“Language desires its own arrival at meaning, but is stymied, stalled, disfigured into telling something other than what it set out to.”

Language enters before it can be understood. The content of the letters is active but concealed. In the first sentence of the story, the narrator warns that “people should not leave looking-glasses hanging in their rooms” any more than they should leave “letters confessing hideous crimes.” The mirror, like the letter, contains not only the risk of representation and divulgence, but also of the opposite: obfuscation, a challenge to recognition and narrative capacity. The symbolic order is groped for, but out of reach; the mirror is approached with an expectation of representation, but instead delivers chaotic méconnaissance. Woolf’s mirror does not function as an agent of mimetic coherence, but precisely as a failure to deliver recognizable forms. As in Lacan’s account, the mirror does not consecrate a stable, unified I. Instead, for Woolf, it leaves two figures—the narrator and Isabella—embalmed in the alienation of impersonal pronouns. A self is not yielded, even through the roundabout process of Aha-Erlebnis—recognizing “That’s me” and thereby understanding “I am I.” Rather, the narrator sees an unrecognizable mediator of meaning—the postman—appear in the mirror and capitulates to the fantasy of effective, albeit inaccessible, representation. The letters possess a talismanic potential to deliver not only the evasive truth of Isabella, but also the world:

If one could read them, one would know everything there was to be known about Isabella, yes, and about life too. The pages inside those marble-looking envelopes must be cut deep and scored thick with meaning. Isabella would come in, and take them, one by one, very slowly, and open them, and read them carefully word by word, and then with a profound sigh of comprehension, as if she had seen to the bottom of everything.

Imagining that Isabella would then take to shredding the envelopes and locking their contents in a drawer, the narrator concedes that “one must prize her open with the first tool that came to hand—the imagination.... One must fasten her down there.” In the absence of the real, the imaginary enters like an understudy. The tragedy of the story comes at the very end, when the narrator suspiciously declares that “Isabella was perfectly empty. She had no thoughts. She had no friends. She cared for nobody.” And, further: “As for her letters, they were all bills.”

What remains unclear by the end is whether the real has entered, displacing the oversize stature of the imaginary with the mundanity of its truth, or whether the imaginary, frustrated by its inability to access the real, has decided to empty out that which it cannot reach. To render it null, to void its content. Woolf’s great accomplishment is in presenting the narrator’s alienation from Isabella not as an obstacle to the story, but as the story itself. Language desires its own arrival at meaning, but is stymied, stalled, disfigured into telling something other than what it set out to.

Woolf’s story is neither a key to Perlman’s poetic career, nor the broader history of therapeutic boarding schools. But what marked those two years more than anything was a profound misrecognition that flourished in an institution tasked with disambiguating, for parents, their shadowy children who have become “unrecognizable, and irrational, and entirely out of focus.” Like Woolf’s narrator, Grove’s therapists and staff exerted greater narrative control when met with its failure. Unable to penetrate the psychic life of students, still moving through the impressionistic throes of subject formation, therapeutic boarding schools revert to diagnostic criteria and poorly qualified norms to tell a story that lacks stable content.

The second volume of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, literally titled “In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower,” was rendered in some editions as “Within a Budding Grove.” What is lost in this version is the distance at which the protagonist is placed from the scene of fertility and life. Cast in the shadow of girls in flower, Marcel is called into the light by the strength of an ambiguous desire for femininity that cannot be easily assigned. In this volume, Marcel is an adolescent, deeply enmeshed (the term used to pathologize my attachment to my mother) with his mother and grandmother, and captivated by a group of slightly older, teenage girls. Blown by a gentle wind toward the sign of the feminine, Marcel does not only desire the girls—specifically: the infamous Albertine—but also his own participation in the scene of girlhood. In his case, the blurriness of desire’s target is not pathological, but part of what compels him out of shadow and into the world. Adolescence involves navigating attachments to the involuntary conditions of one’s early existence, and the will to invent a new one. The security of the universe one entered as a dependent enables the audacity to leave. Haphazard activations of desire and experiment provide a map of one’s wishes for the future. In theory, Grove sought to provide support for teenagers who struggled to move through this process; in practice, it held adolescence hostage in a barren, surrogate world where psychic life was pruned, just as it began to bud.

[1] Paris Hilton’s 2020 documentary, This Is Paris, brought attention to the abuses of the troubled teen industry, as well as advocacy groups like Breaking Code Silence.

[2] I add this non-psychotropic medication because of a discovery in recent years that it causes suicidal ideation and hallucinations, especially amongst minors.

[3] Caring4youth.org/872.html#:~:text=The%20cost%20of%20tuition%20(education,rate%20of%20%246075%20per%20month.

[4] Leach, Samantha, The Elissas: Three Girls, One Fate, and the Deadly Secrets of Suburbia, (New York: Legacy Lit, Hachette Book Group, 2023), p. 98.

[5] “Connecticut facility recalls ‘success story,’” The Royal Gazette, December 10, 2019, www.royalgazette.com/other/news/article/ 20191210/connecticut-facility-recalls-success-story.