Composite Case

The fate of the children of psychoanalysis

Hannah ZeavinMoyra Davey, Jane, 1984

In the home where its key texts were written, perched on a ladder, the fifteen-year-old Anna Freud began her study of psychoanalysis. By 1910, Sigmund Freud had completed some forty articles and several of his famous books. Young Anna perhaps fingered the gold chain on her neck, neatened the severe middle part of her hair while reading his seemingly endless volume on dream interpretation. Then, leafing through those hundreds of pages, Anna spotted her name.

Among her brothers’ and sisters’ dreams, there appeared one from when she was just nineteen months young. Anna had been ill throughout the day, vomiting. She wasn’t allowed to eat. Asleep, she listed out, according to her father’s record, an extensive menu of foods, starting with her own name: “Anna Fweud, stawawbewwies, wild stawawbewwies, omblet, pudden!” Sigmund then interprets the dream quite straightforwardly as a double, split desire for strawberries in two forms (both cultivated and wild). She wanted the kind that caused her sickness and persisted in her infantile desire for more anyway. Because her nurse had decided she was ill due to them, her dream wish was “thus retaliating … against this unhappy verdict.” Anna’s desire for wild strawberries, Freud writes, illuminates what he called “wish fulfilment” in dreams. With evidence from his children’s utterances, he tells us that the child’s wish was for a nonsexual kind of forbidden fruit. By possessing it in her dream, Anna stayed asleep, and for Freud, this is the function of dreams. Dreams are the one place where we can have what we want.

Outside of the dream, now an adolescent, Anna may have suffered and affirmed the shock and delight of recognizing herself in the sentences written down as theory. She was a little experiment, the terms of which were only now being clarified. Unwitting, Anna had fed her father the strawberry dream. As a father, Freud gave his daughter her privacy while, as a theorist, he made her an example.

To make his theories, Freud turned not just to his patients but to his own family and intimate circle.

The father of psychoanalysis was also a father of a family. His laboratory was not just the clinic but the home. These spaces materially overlapped, with the salon adjoining a family bedroom, and the waiting room through the wall of the salon. A friend of Freud’s recalled, “Regardless of which bell one rang,” for apartment or for office, “invariably the other one opened.” To make his theories, Freud turned not just to his patients but to his own family and intimate circle. In Interpretation of Dreams, Anna was stitched among others—her siblings, Freud himself, their family friends—to form the basis, the very evidence, for the workings of the unconscious. It was precisely this kind of woven story, plucked from those nearest him, that allowed Freud to move swiftly from, say, his particular daughter to a clinical case to a universal claim about the human psyche. This experimentation and transposition—of a real child to a generalization—wasn’t limited to Freud. His subsequent followers developed new theories of infancy (and thus human life) on the grounds of their own children. Psychoanalysts have long watched their children—noting their development, their dreams, their symptoms—to universalize the Family from their families. Together, these child observations form an endless corpus that is an exquisite psychical corpse, wishes and fixations stitched to phobias, running the length of Freud’s Standard Edition.

We’ve been told that psychoanalysis was elaborated on the grounds of adult patients subjected to a kind of time warp—Freud invented a method centered on “infantile states” (what must have happened, via extrapolation, when we were babies or children)—and that there was almost never a real child in the consulting room. The only child accessible was the adult in reverse, through the archeology of the subject. Instead, as Anna discovered time and again, this is not exactly right. True, only one child patient spent time in Sigmund’s consulting room, but Freud was engaged in child observation: he extrapolated something of their unconscious mind from their play, their speech, their little dreams. Deployed as a form of evidence that couldn’t be admitted scientifically, these child observations were presented as universal precisely to occlude their excessive, intimate specificity.

*

All parental labor has elements of contagion. This is what is meant by inheritance, both psychical and material. Psychoanalysis as a profession is centered on the family—and its violence, even its incestuous wishes, fantasies, and structures. It might appear that having the high examiner of these issues in-house might free a family from them, but as a culture, we’ve decided instead that it only increases discontent. The long-standing trope of the analytic parent and their overanalyzed child has circulated for decades, manifesting in myths about such parents not only fucking up their children but driving them to madness. I trace the elaboration of this myth to a kernel of truth: Sigmund Freud did indeed bring the clinic home, and his family into his clinic, most overtly when he saw his daughter Anna on the couch, but also all the time. In the intervening century, we’ve been treated to endless variations of negative stereotypes of the psychoanalyst—the headshrinker, the quack—some inflected by antisemitism, some not. The assumption is that if you draw the short end of the stick and are assigned one of these perverted people as parents, you have no choice but to follow in their footsteps. The very quacks meant to cure us—no, re-mother us—can’t do it any better themselves and make their children all the worse for it—so says the popular imagination, eliminating the expertise of the experts, however fleetingly.

My parents were, or so I thought for two decades, human polygraphs

I am sure that, for some children of psychoanalysis, this is true. Yet the problem for the child of the analyst is not necessarily true to the myth. The myth suggests that, through overanalysis, the parent becomes increasingly entangled with the child, the Oedipus complex compounds. Or, as some imagine, the child is treated as a cold scientific object and then emerges too hot under that terrible pressure to be all right angles and math of the psyche. My childhood among the analysts was sanguine, loving, filled with the ordinary crises that present whenever people try to live together at duration in the world as it is. I have no need to adjudicate the state of My Childhood. Instead, I want to make a case for how the clinic toughened my childhood, rubbed against the grain of something generally smooth, made itself known.

My parents were, or so I thought for two decades, human polygraphs: so versed in the workings of the mind that I felt reduced to transparency in their presence. When the blood of trouble circulated, I figured my parents’ iodine trace as immediate, the complaint’s origin precisely and swiftly located. Once located, it might be removed. I wanted this, for who, once ailed, doesn’t desire to be fully apprehended, to be cured of problems large and small via attention and sent on their way? Many people don’t want this, I know, yet I did, and stunningly, I often felt I was.

The family operates with an attention economy—there were five of us. But the number that matters is three; three siblings lying horizontal in one plane of competition. It cannot be helped that this relation was and is perforated by envy in its love. If envy mixed with attention, we each had a means of securing the latter. My mother once told me that every night—long after we were little, long after we left home—she went to bed with a rosary of names and cycled through them, pausing to decide if each was well enough to move on to the next: Hannah, Ivan, Isaiah, Hannah, Ivan, Isaiah. The list remained the same, while the emphases, the footing, the intonation changed in the private apostrophe, for she wasn’t addressing us but herself. The father of my two friends—sisters—said to me once, abruptly, in their presence but likely out of earshot: only one daughter can ever be okay at a time. One would cry, the other would sleep. Then switch. A perfect sororal rhythm. He said it had been so since infancy. To be the object of concern was to be the object of care, in their family and in ours. It carried rewards, namely, the great prize of attention in a family that couldn’t offer it fully, evenly, among its constituents. Each according to their needs, and we all had them. It seemed patients might get the most careful, rigorous observation and not us—attention was paid for elsewhere.

Some clinicians come home from this scene unmarked, able to fully subscribe to the notion of a rented hour and thus unsubscribe at the end of it. A friend recently said to me that when his final session of the day reaches its limit, he heads home, cracks a beer, gets on the floor, and plays with his kid. He doesn’t think about his patients again till faced with them. Not so for my parents, and this I honor. The rented hour has always been a false construct when braided with the truth of analytic care. Some days we were picked up at our respective schools by our parents, taken home or shuttled around town. Others, they might come in late, far behind the eyes, tired, glad we were fed by someone else, warming up, as if on tape delay, to a different set of demands.

The question remains, how different?

*

Moyra Davey, Eric, 2017

The married Soviet virologists who pioneered the oral polio vaccine first protected their children via their only means: experiment; they laced sugar with a dose of weakened but live virus. Their product was reality tested, then codified scientifically. Then it was given to the nation. Later, one of their children recalled that he ate polio “from the hands of my mother.”

Similarly, psychoanalysts applied their processes to themselves and to their intimates first, in the home, in a weakened dose. But the experiment also went the other direction: the children provided the data necessary to elaborate the evidence of efficacy. Freud wasn’t just watching Anna (and Sophie, Mathilde, Ernst, Oliver, and Martin), but also the children of fellow analysts. If his own child wasn’t available as the engine of a particular theory, the child or grandchild of a colleague would do. When he couldn’t watch them in vivo, he had their parents take notes and mail those notes to him. Psychoanalytic theories and myths are predicated on quite a small subset of the Viennese bourgeoise; they called themselves the Wednesday Society. In this sense, the criticism of psychoanalysis—that it only treats its world-historical Victorian family even as it claims to treat us all—is all too correct.

If Freud’s other five children were raised, at least for a time, in the absence of psychoanalysis, Anna had no such before. Both Anna and “the Project,” or what the earliest incarnation of Freud’s psychoanalysis was called, were born in 1895. These twins—the theory and the child—were about seven years old when the meetings of the Wednesday Society started. In 1902 Freud, at the suggestion of his patient Wilhelm Stekel, began to gather his followers for little collaborative sessions where he taught the new field of psychoanalysis. The group was small and informal at first, conducted in the ever-shrinking apartment that held Freud’s family and his professional work. Freud had already debuted his notion of the unconscious and published insights from his analytic work on himself, achieved primarily in correspondence with his Berlin-based best friend, Wilhelm Fliess. These insights were autobiographical, as is all analytic work, and socially collaborative.

Once Freud’s findings circulated, and thus were no longer confined to his approving coterie, they were deemed improper, too revealing. Freud was further maligned by his mainstream medical colleagues, who treated him like, as Freud reported, a “freshly painted wall”—they wouldn’t touch him. Yet there in Berggasse 19, Freud’s first four, and then later seventeen, disciples gathered around him and his family life. When the Wednesday Society met, no children were present as members of course, but they were surely coming and going, pacing the flat beyond the salon. Eventually, there was a move to formalize, to collect things like dues, attendance records, and meeting minutes. Psychoanalysis and Anna were both twelve years old when the meetings were made more official, reformed under the auspices of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society.

Lacking the requisite number of patients and data that could be understood by medical peers as evidence, Freud and his followers had to make do with all kinds of analysis not bound by the consulting room. The Wednesday Society psychoanalyzed those living and dead, they psychoanalyzed public figures (now codified as an ethics violation under the Goldwater Rule), and they psychoanalyzed themselves, some via confession, others from diaries, others by recounting their travels down that royal road to the unconscious via their own dreams. Later, these activities would be hived off as improper, as wild analysis, but early theorization could not have occurred without them. Childhood was an essential gap in the evidentiary foundation of psychoanalysis, so they also trained their analyses on those under their care. To substantiate the Oedipus complex, they needed evidence from children themselves. Such evidence could be anecdotal, told as little trivialities from the home front. The serious work of proof, and the burden of it, fell to the clinic.

Freud asked his Wednesday Society followers to send missives concerning their children, which he would then scan for evidence and enter into his research. These missives dot Freud’s writings both explicitly an implicitly; he returns to them for more than a decade, publishing them up through Totem and Taboo in 1913. Once, Freud even turned the mailed notes into a paper, “Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-Year-Old Boy,” by which the Oedipus complex found some clinical substantiation. Beneath it all was little Herbert Graf, given the pseudonym Hans, who was only seen once in the consulting room for the duration of the treatment.

The Hans case has been ridiculed as a spectacular instance of confirmation bias, and largely forgotten clinically, though it still retains some standing in the psychoanalytic imagination. The case centers on the analysis of a five-year-old’s phobia of horses, their penises, and the outdoors (he had become agoraphobic). The Hans case started when Max Graf, one of Freud’s disciples, wrote casually to Freud of his son, honoring his teacher’s request for information about children’s psychosexual development. The family had responded to Freud’s interest by keeping a diary of Herbert from his infancy through his toddlerhood.

Freud was by then already a mentor, doctor, friend, and perhaps paternal stand-in within the Graf family. Freud had first treated Graf’s wife, Olga, a patient he’d inherited from his own mentor, Josef Breuer, and whom he likely treated for free when her parents wouldn’t pay for care, even in the wake of the back-to-back suicides of her older brothers. Olga’s praise of her treatment and of her doctor is what drew Max Graf to Freud’s office. Max even sought to secure Freud’s diagnostic blessing before deciding to marry Olga: Max wanted to know if Olga was cured enough to be a good match for him. When the marriage became “disastrous,” Freud urged the couple to have a baby—Herbert. Recalling the scene in his forties, Herbert’s wife described his family as “Freudian to our core.”

Before “Hans’s” troubles began, his father was already reporting little trifles of insight and speech from the nursery to Freud’s office. Some have interpreted the meticulous journaling of Herbert’s development as payment in kind for Olga’s analysis. Then Hans’s fears became significant and impeding around age five. This was a nervous disorder, euphemized by the father to his son as a bout of “nonsense.” Graf wanted to put a stop to it, and get his son analyzed by Freud, but the boy wouldn’t leave the house. The result was a strange cure: Max Graf would take notes on his son, then send the material to Freud. Freud would interpret, and write back to Graf, telling him what to say and how to say it to his son. By all accounts, the little treatment got Hans back to sense.

Much has been made of the case, namely what is novel in it (child patient, postal cure) and what went wrong (what we would now call ethics violations). Both historians and clinicians have conducted forensic work on Little Hans, showing that Freud failed at any objectivity. Not only was the case overdetermined by Freud’s relations with the boy’s parents, but he wanted too much from it at the outset—namely, a child to stand as evidence for his new theory of psychosexual development (oral, anal, genital phases) and the Oedipus complex. In his Three Essays of 1905, he had illuminated the infantile sexuality present in thumb sucking, nursing, and sibling rivalry, drawing on the home to fund the clinic with evidence. Now he specifically needed a boy to hold up as proof for his new theory of fantasy. Herbert, whatever really went on with him, was close enough to turn into a perfect, concrete mapping of Freud’s newest venture, the basis for a case study that Freud rushed to publication.

*

My son demands that I chase him. He wants me to be both predator and enveloping mama, and he will be the little bunny. “Chase me,” he exclaims. I do. As we near the completion of a loop, he turns back around and shouts, “Save me, Mama, a predator is after me,” and I scoop him up and say, “Of course I will protect you.” We march off to our burrow, the couch. Then the demand comes again. “Chase me.”

Like Max Graf passing his anecdotes to Freud, I know where my debt is, and I will pay it back.

I understand that I will protect him from myself, as best I can, from the part of me that persecutes. I also understand that this is impossible, the predation has already taken place, and that this is what he is showing me. In the Bible, Solomon lays a test, a trap. Two women come forward to claim a baby. He offers to cleave the baby in two. The woman who refuses is understood to be the true mother, whatever that means. Almost all children fail this test—they must, to preserve their sanity, divide their parents. We are splitting creatures, trying to preserve the good from being touched by the bad.

I recount these stories to my mother, alongside my child’s sudden bravery around heights or some other triviality we treat as holy. She delights—then she remarks, “See, it’s…”—then launches into a Kleinian formulation, leaning in like the manicurist in The Women, in giddy spirits, making a confession that takes the other as subject instead of oneself. She offers me an interpretation—

“You see, Hannah, what he is doing is splitting”—enthusiastically declaiming. As if it is not evident by my choosing to recount this particular scene to her, I know to whom I speak. I know I am bringing her the gift of a dead bird, dropping it at her feet. Like Max Graf passing his anecdotes to Freud, I know where my debt is, and I will pay it back.

When I was a child, my mother hadn’t yet come to Klein, who now is her lord and savior. The Brits started to visit our home when I was in latency, and she would go there, too. She has stressed, privately and then to me, that she was glad she didn’t know Klein’s work well when raising us, that the temptation to observe us more carefully for our aggression would have been great, and it must be said that remarking on the grandchild to his mother is different than to remark on the child to herself. This my parents never did, not in this fashion. On the occasion of chase me/save me, my mother’s interpretation, and mine too, is one Melanie Klein drew from her own mothering, her babies at her breast, one of whom would grow up and later denounce her as Hitler while still becoming a psychoanalyst herself.

Why I tell my mother and why she is pleased has to do with my possession of her and her of me. Somewhere along the way, I decided that, if I were to be shut out of the bedroom, I wouldn’t be kept on the wrong side of that other closed door, the consulting room. If she might remarry an analyst and I couldn’t Oedipally win, I might give it the good old college try and at least pull a draw—equal her husband as officemate if not her bedmate. Now I am furnishing my child as data for her work, a little confirmation, then sticking this scene in my work, evidence for my own theorem that we were hers. Sometimes she admonishes me: don’t say this in earshot of your child. Just tell me when he isn’t there. I blanch, caught somewhere I’m not meant to be, in the middle of my own little enactment.

*

Freud was an archeologist of the psyche as lived in singular subjects, but he also mixed up his bones. If in the Hans case theory preceded its examples, Freud, too, played with intermixing the patient and the child. Rather than just digging and dusting, he was equally a filmmaker, taking two real-time films, one of his children conducted off the clock, and the other of adults in the clinic. He spliced them together to make a transpersonal, multitemporal being convenient for his theory, which bares the trace of this cleaving. We can only speculate on some of the glitching effects: an adult patient, raised in say the 1870s, grafted onto the psyche of a child born in the twentieth century; the patient a site of countertransference, and the child a site of paternal love. And yet, these little bindings are the basis of psychoanalytic knowledge.

To make a composite is the practice of combining and remixing patients with similar psychopathology such that they’re protected from discovery, protecting patients from that shock Anna experienced at fifteen of being recognized and, invariably, turned into a case study example. The brute recognition of the facts of a case, described as such, can destroy the veil of the analytic relationship. It can also be delightful: the writing as a sign of attention spent off the clock. The composite case has other virtues. Because it accumulates several patients to type, it’s more robust as evidence. On the other hand, move or pseudonymize one detail errantly, and the whole case can ring false, fall apart. Creating a psyche whole cloth is difficult to do.

Children in psychoanalysis provided the material for psychology’s first composite cases, even as they aren’t marked as such. Eventually, composite cases came to prominence and became the default, in the latter half of the twentieth century. But long before this, the famous cases we remember by individual patient were, in a sense, composites under cover, masquerading as single origin. The children who float through these case studies—Wolf Man, Rat Man, Dora—are protected by being submerged. What remains is a taxidermized patient, held as ideal, as type, stuffed with the data of the home to give it a lifelike fullness of appearance.

Far worse uses of children abound in the sciences, and we can be glad Freud, largely, gathered his evidence passively. The doctor-father of Daniel Paul Schreber—who would grow up to be a touchstone for Freud's theory of psychosis—tested disciplinary devices on his child and others until, as some have it, a generation of his subjects went mad and he fell to authoritarianism. John Watson tortured Little Albert B. in 1920 to prove that, indeed, you can elicit a trauma response if you try hard enough. Wendell Johnson and Mary Tudor conditioned orphans to have speech problems by degrading them as they talked in 1939. Dr. Lauretta Bender subjected children to electroshock treatments to both prove schizophrenia was in evidence and cure it, recalling Charcot’s tests of hysterics (you’re only sick if my treatment cures you). For all his methodological and personal faults, Freud did not design or oversee any such cruelties in experimentation, nor is it my contention that there is a covert, if less serious, ethical problem with this evidentiary sleight of hand.

Since Anna’s youth, children have only become more observed, and more aware of it. The art of baby watching—of lay infant and child observation—became increasingly professionalized in the early twentieth century until it was a science, formulated by Freud’s own disciples and taken up across psychology. With the proximity of patients to analysts, analysts to families, teachers to followers, followers to children, the laboratory for early psychoanalysis departed the clinic before it could be contained there.

The children of psychoanalysis were nonetheless subjected to something like the observer effect—in being studied, we change our behavior. The child psyche is no more complicated than any other genre of case study, and its specific kind of intimate evidentiary regime has a long history. All patients in psychoanalysis are, to some extent, phantoms invented by their doctors, and the case study has been understood as the formation of phantoms who exist: it’s a genre that produces “the idiom of the judgment,” as Lauren Berlant put it in their essay “On the Case.” Or perhaps it is a transpersonal phantom that doesn’t exist who is raised from the evidentiary corpses of persons who do. Berlant continues, “As genre, the case hovers about the singular, the general, and the normative … to generate knowledge in the absence of a theory.”

Yet, especially when it comes to the case study of children, psychoanalysis faced the converse problem: Freud sometimes generated a theory in the absence of evidence. It could not be independently verified. To overcome this, Freud’s theories of childhood development, based partly in child observation, went further. He didn’t just take up the idiom of judgment; he judged and then found his idiom.

Only, this was never to be known, and when it was, it became the wraith of the practice. The psychoanalyst has lived in the shadow of disconfirmation because their practice has; it is what makes them hungry for the slightest confirmations, even in family. Psychoanalysis has, since its early conception in Freud’s living room, been threatened on all sides. This may sound like the textbook definition of paranoia—one written by Freud himself. But it also has historical veracity. As if psychoanalysis was anathematized for the sin of giving us a new theory of sexuality, the practice has been under siege since its very beginning. In brief, the commination, that recital of threats: the radicalism of psychoanalysis has not been well received and thus it has donned a conservative cloak; it is neither particularly expedient as cure nor friendly to the rhythms of capital, yet has been offered in large part only to the wealthy. In many of its uses, especially after Freud had gone, it extrapolated a theory particular to its time and moment and class and made it universal, creating a normative white psyche even when that psyche is one of many and in disrepair. Across and intermixing with all these menaces—many self-generated—has been a lingering suspicion of quackery, charlatanism, and bunk. We may have exchanged the charge of mesmerism for the charge of unsupportable, unquantifiable navel gazing, but the charge remains.

No one knew more the power of self-censorship than Freud: he based the theory of the unconscious around the premise that it rules everything. In the name of public scienticity, psychoanalysis withheld its evidence time and again by not venturing its bolder claims, its left politics, and by not submitting itself as quite evidentiary. When the parent-psychoanalyst then has ample evidence in their home, they are all too delighted to privately turn their baby into its proof, as if to say, here is my confirmation, unsought and unbiased, but exultantly received.

The baby is thus beloved: his majesty, the evidence. But this must be a matter closely guarded—evidence can only come from the clinic, from whence comes our help. A medical doctor doesn’t need to turn to their privacy in this way. They don’t exclaim when the child walks at twelve months, or at least don’t take it as a confirmation of pediatric science. They don’t need to. Their science has been confirmed in the public mind. That the baby has aggression in infancy has not—is not even agreed upon by psychoanalysts. And yet, watch a baby nurse, see how it terrorizes the chest.

Sharon Bridgforth writes, “Those things that you know but you don’t know how you know them, are true.” The child provides a way of knowing. For the analyst, perhaps especially one that doesn’t see children in the clinic, to come home to them is to see their theory confirmed, and this provides a salve on the burn of the accusation of quackery, like a miracle provides evidence of the divine to a believer surrounded by the faithless.

The analyst is there to save you from your parents and from how they’ve gotten transformed inside to bad objects that continue to mete out punishment long after the punishment has ended. How can you resolve to fix the problem when both roles are played by the same mother? She must predate and save simultaneously.

*

Moyra Davey, still from Les Goddesses, 2011

My parents didn’t interpret me to my face—or at least, I was never transformed into a case before my own eyes. This was held back, if there was ever an urge, and I imagined it happened at night, when they were lying beside each other, scrutinizing me even when I wasn’t there (convenient, isn’t it, to imagine the other talking about us where we are forbidden from going). I think at the time, once I understood more of their work, I saw these neat formulations as a gift given only in the clinic, one we were deprived of at home. However, there, they demanded the materials that precede interpretation. This all three of their children agree on. Isaiah, my youngest brother, says, “Nothing was real until it was spoken.” Ivan jokes glibly, “Roots—not fruits.” The demand for the fundamental rule—to communicate verbally and freely—was in effect. Recalling Rancière’s critique of Barthes’s punctum/studium divide—that to narrate the wound is to study it and thus cauterize it—feeling a priori was, Isaiah felt, meaningless. Upset and pleasure became significant as we considered them. This meant that, for complaint, one needed the hard proof in speech, not in symptom.

Then, alas, de-idealization came, as Winnicott tells us it must. I knew soon enough that my parents, like any polygraph, could be triumphed over. How, then, had I mistaken their ability to read my eyes dilating, my breath contracting, assuming no privacy where perhaps there was too much? My parents were, after all, delighted, like most parents, to be gently deceived. I felt, adolescently, constantly scrutinized, but gloated that this was a prize even if it carried consequence. I’m speaking of psychic reality—a fantasy and a wish and the real colliding, which might account for the paradox. If the parent never knows their child, not fully, the child is ever more helpless to know their parent. Scrutiny, the lie detector, all of it can come from within.

In response to my own demand for a mistaken, mystical, enigmatic care, one I all at once learned was impossible, I went the other direction, or every direction all at once. I tried first to make their job easier. I backlit myself for them, lay right down on the light box, named every feeling, told every story. When this failed to produce what I wanted—for what I wanted was impossible—I went behind the eyes, departed home for new others, my objects refound. If I could manage, under such observation, to reclaim a small privacy, tell a little lie of my whereabouts, and not get caught, this was another prize. I wanted to be known completely or disappeared completely. I still contend with my logorrhea, brought on in the company of hard silence; I still contend with shutting myself away.

The problem might be simply put as this: to have an analytic parent means to have a parent who is trained in human behavior without that resulting in mechanistic knowing; their schema doesn’t help them suddenly overcome their own humanity. The statues of all parents must topple, but the fall of the analytic parent, as the child is disillusioned, is a further fall. I would ask them as a child: “Can you stop it and turn it off?” They said, “Yes, of course, darling, we don’t analyze you,” rushing to reassure. I asked the question again as an adult and they answered honestly: not really, no. These are not contradictory answers; when they listen, they listen as they have learned to do. Events from our life wound up in clinical works, right alongside patients, if demarcated as different, held together by technique, by ear. I never lay on the couch of a parent, save to nap, yet they were listening to me as doctor and parent at once.

*

Freud did blur clinic and home in the clinic once, in the name of cure. He treated Anna, which Ellen Pinsky calls the original boundary violation of psychoanalysis. In psychoanalytic norms, the reason for this boundary—and the practice of referring patients away from the family and its networks is, in part, that any analyst is a site of transference, very likely a parental one. Anna and Sigmund conducted a unique experiment: What if there is no transference save that between parent and child? No object refound, only object.

While the father treated his daughter, the rest of his practice carried on. Other patients, gatherings, contacts, writing. In 1919, Freud published a strange article, “A Child Is Being Beaten,” which chases after the origins of masochism. Freud tells us that many patients came into his office in the preceding period with an obsessional fantasy to which they most frequently gave the passive formulation “a child is being beaten.” The phrase referred to a masturbatory scene, a fantastical one. The patient would imagine a child being beaten and get off.

Freud wanted to know why and how—what made it so exciting. Freud offers, as evidence, six patients with this fantasy, but Freud assures his reader that many more patients have this same formulation on their lips at climax. To answer the riddle Freud set for himself—why do many patients all share the same utterance— Freud had to concretize the phrase, to read it like someone just learning how to read. He breaks down the parts and sounds it out. He begins by thinking about a child. The theory of psychoanalysis contributed to the understanding of many psychic mechanisms. Here, most key, is repression. The patient in the consulting room only remembers that, currently, they are besieged with a strange fantasy. Freud knows, archeologist he, that there must be layers behind and beyond that phrase to make it function the way it does.

Freud lays out his case. To do so, he travels through the sedimentary layers of the mind, going back to the beginning to come forward. By the time Freud publishes his case—and we read it—the evolution of the fantasy is split into three neat moments of development. The fantasy moves, as they are wont to do, from a kernel of truth—here, witnessing a child being beaten—to an intermediate phase that the patient has no conscious memory of, to its final form, “a child is being beaten,” which Freud hears about from the couch.

Freud’s evidence is multiple but not composite, as far as we know. He presents his six patients anonymously, turning the lion’s share of his attention to his “girls,” now women, four of the six. The fifth one is Anna, his daughter. Freud, of course, doesn’t say so—he can’t. It would break confidentiality, and it would produce problems given the exact nature of the fantasy, as we will see. He proceeds neutrally into a theory that articulates functions as follows.

Phase one: “My father is beating the child.”

Freud recovers for the patient that the root of their fantasy comes from childhood, as all central masturbation fantasies might. This phase centers on our patient, as a child, witnessing their father beating a child. The child being beaten is, likely, real. But the child is not our patient; the patient is not remembering coming to harm themselves. It is their sibling. The child being beaten is the child with whom the patient feels rivalrous, envious, would want to see being beaten. (In the case of patient D, when Anna is the child witnessing this scene, it is Freud doing the beating.) This is the moment, as Juliet Mitchell has taught us to mark, when Freud avowedly turns to the “horizontal axis” of the family, that lateral plane of siblinghood, to tell us that siblings and sexuality are more intimately linked up around the Oedipus complex than we might otherwise think, but also generates its own peer-to-peer violence. It is not just parents all the way down (and up), but the overlaid sibling triads around them, behind them. Not just the rival as mother, or rival as father, but other potential Oedipal winners—siblings whom we might want to defeat or replace—that drive sexuality.

Phrase two: “I am being beaten by my father.”

This is now certainly, for Freud, fantasy. Knowing what we know about which child and which father are in question in this scene—that is to say, Freud, Anna, and one of her siblings—we must deduce that Freud is claiming, without saying so, that he never harmed Anna (even as, he therefore suggests, he did beat one of his other children). Nonetheless, our patient fantasized that she was the one who was beaten. This is where fantasy turns erotic: “High degree of pleasure .. of an unmistakably masochistic character.” In a moment of glorious Victorian phrasing that delays its object to the very end of the sentence, Freud writes: “there is almost invariably a masturbatory satisfaction—carried out, that is to say, on the genitals.”

We learn that, like wisteria growing over a house, daydreams become the facade of fantasies. The patient doesn’t remember this phase at all until their psychoanalysis; they only know of their present daydream, “a child is being beaten.” They have forgotten that they got off on being that child in their own mind, centering themselves, replacing their sibling, being the object of violent attention. Phrase two is incomparably important because this is the repressed phase. When the patient comes to Freud, they remember phases one and three, but not phase two. This is what Freud has uncovered.

Third verse, same as the first: “A child is being beaten.”

We are now back in Freud’s consulting room, where the patient comes in, free-associating to their passive statement, “A child is being beaten.” Freud’s starting place is also where he ends, mystery now solved. In the patient’s fantasy now, the father is disappeared, and in his stead are multiple children. Our girl-patient is looking on. The beating, Freud notes, can be exchanged for other means of humiliation, but the salient point is that, phase two having been repressed, the scene is an active voyeuristic masturbation fantasy. Again, although the girl-patient is singular, she is always part of a class, not a composite exactly, but a chorus. And, anyway, she is no longer a girl, but recounting girlhood; this is not a child testifying.

*

A child is being beaten, but not oneself. A child is made into an example, exhibit E to be precise, tucked in among the rest. Any story can be used to model and teach a concept, an interaction, a genre of feeling. In my family lore, we have our own “a child is being beaten,” which we call “the cake story.” It goes something like this: circa 1961, when she was five years old, my mother saw that there was a Pepperidge Farms cake defrosting on the kitchen counter. This was the kind of cake, she recalled to me several times when I was a child, where you could peel all the frosting off. My mother could not resist the temptation: she denuded the cake, ate all the fondant.

My grandmother, Barbara, was the daughter of Hungarian and Russian émigrés. She was a very beautiful housewife (she looked like Ava Gardner) and became a mother at nineteen. She needed a great deal of care—brittle is the word my mother arrives at, but brittle where breaking is evidenced by violence. My grandfather, not yet American, was a doctor doing a residency stint in Nebraska, and that’s where he met Barbara. He was a father in the worst sense, absent and yet omnipresent, all violence and excitation, a gambler, likely manic-depressive.

A patient is being analyzed. A patient, but not me.

Upon discovering that the cake his wife had defrosted was perfectly marred, my grandfather called to his two sons, Bob and Michael. Though he usually blamed the middle child, Michael, for everything (calling him a “bad seed,” chasing him with knives, beating him with whips), he commanded both boys to lower themselves into a squat in the kitchen in front of the ruin of the cake until one of them confessed. Except neither was the culprit. Standing just beyond the door to the kitchen, watching this scene, my mother is in the position of one of Freud’s patients, of Anna. She is watching her rival-siblings being beaten. But instead of feeling sad or guilty or worried, she feels insidious excitement—her term. My father is beating my brothers, and not me. Despite her pleasure, she finally copped to the crime. Little Lynne had eaten the fondant. Her father brought her to him and took his two fingers and tapped her on the wrist. That was her punishment. He loves me and doesn’t beat me, but perhaps he doesn’t love me because he doesn’t beat me.

To be the child of a psychoanalyst is a form of “a child is being beaten.” A patient is being analyzed. A patient, but not me. And just like a child, the wish is to become the object of attention—scrutinizing, unraveling—but nonetheless gratifying. That’s where my insidious excitement lies. For the children of psychoanalysis, this wish, to be the patient, like a wild strawberry, may be fulfilled despite making us sick.

*

Moyra Davey, Smoking 1, 1987/2016

In 1922, just three years after “A Child Is Being Beaten” made it to press, a twenty-seven-year-old Anna Freud came before the Wednesday Society, now called the Viennese Psychoanalytic Society, for it was now yet more formalized and had protocols. It was her turn to try to qualify as an analyst in her own right. Then, as now, before giving the talking cure, one must have been a successful recipient of the same. Additionally, to qualify, analysts had to present material to the society. Having never seen a patient, Anna turned herself into her own “patient” and presented herself this way. A secret self–case study.

The paper Anna presented before the society, entitled “Beating Fantasies and Daydreams,” makes it painfully clear that Anna was indeed one of Freud’s patients in “A Child Is Being Beaten.” In the paper, Anna presents the actual child of an analyst under the guise of a universal theory of masochism. She opens her contribution thusly: “In his paper, ‘A Child is Being Beaten,’ Freud deals with a fantasy which, according to him, is met with in a surprising number of persons.”

To elaborate her own self, she must cite her father’s use of her to make something bigger, to be but one of a number of persons, and part of an abstract Person. She became world-historical and generic while also just wanting her father in that quotidian way psychoanalysis tells us all little girls do. Except there was nothing generic about it—it was robbed of the potential for banality.

After citing her father to her father to gain his approval, Anna begins the tricky work of nestling her contribution within his. She defers to him, makes her contribution dependent on his, even as his was dependent on her case. Anna goes on to describe the experience of her single “patient” as a perfect illustration of her father’s “A Child Is Being Beaten.” She may share the fantasy with others, but she claims herself as the perfect stereotype. In the consulting room, as Patrick Mahony writes, “Freud was in the process of symbolically beating her and compounding her beating fantasies.” Anna’s presentation to her own father-analyst, surrounded by his disciples, is the climax of the narrative. She comes before him having been beaten, at least fantastically, to reclaim her own case study from him in a performance of perfect obedience. The society gathers round, stepping in as the group of onlookers, that mob of children from the beating fantasy. They watch her as she beats her father and he beats her.

*

Beyond being Freud’s daughter and chief protector and an analyst in her own right, Anna Freud is remembered as a consummate knitter. While some analysts eschew any pronounced form of the bodily or libidinal in sessions—won’t go so far as to drink water or sip tea—to be Anna’s patient was to hear the constant clacking of needles while describing and associating, a raveling accompaniment to an unraveling. Anna’s whole career was a living memorial to her father—both before and after he died. In her knitting, there was this less obvious memorial to the women of her family, to the feminine work of the Freuds, especially the mother she never fully had, and her beauty of a sister Sophie.

Anna would knit clothes, particularly for her stepchildren, whom she lived with alongside fellow analyst Dorothy Tiffany Burlingham, the last Tiffany heiress. When Dorothy first came to Vienna, it was to see Freud’s disciple, Theodor Reik for treatment in connection with one of her children’s psychosomatic disorders. She eventually became Freud’s patient; Anna, now a proper analyst, treated those children. The two women became partners; wives and analytic siblings at once, the mother of her patients, the doctor of her children. Anna, too, it must be said, treated her own children, but in reverse. Her patients became her children. She re-mothered them in the clinic and then mothered them at home. The analysis of the children who eventually grew up apparently never terminated.

To inherit psychoanalysis is paradoxical: it is the only psychological theory that seeks to separate what was put into one from oneself, even as it comes from another.

It is tempting to see this as an accident, the kind psychoanalysts believe in, a driven reenactment. Anna did what her father did; having served as a specimen for him, she took her children up in the same manner, crossing and braiding relations. Yet this is too vulgar a Freudian reading to let stand without adding an additional one. For the children of psychoanalysis, it seems that there is a temptation to follow into the family firm, and although that’s true of many specific labors across the class spectrum, when the children of analysts do so, it is a form of available incest, and one that many of us cannot resist. To become composite with our parents, to be one of their patients.

Psychoanalysis is a theory of inheritance. We might make our own history but, as Marx tells us, we don’t make it as we please. There is no self-selected circumstance—just transmission. To make psychoanalytic sense, the theory, the science, is not to be lost. In my own work as a patient, I was often admonished by Dr. G. for using the vocabulary of psychoanalysis to describe my own feelings: splitting, persecuted, and so on. She would press, “But how did that really make you feel, Hannah, try again. Don’t intellectualize.” I would quickly get frustrated: we had to name our feelings; the language we named them with, at four, at twelve, fifteen, was from this discipline. Why should I say I am sad if I know better, more precisely, from whence my trouble is located? I have no better words certainly, but also no alternative. To inherit psychoanalysis is paradoxical: it is the only psychological theory that seeks to separate what was put into one from oneself, even as it comes from another.

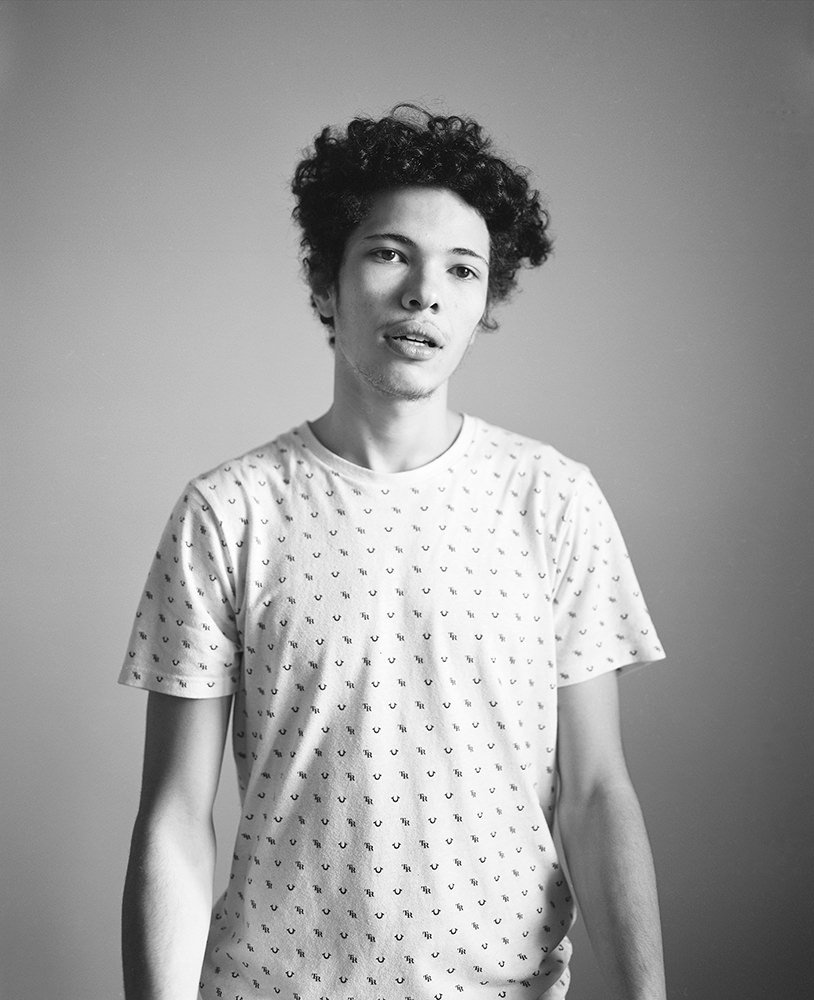

The author and her mother circa 1995, by Moyra Davey

No matter how singular we might wish them to be, the patient is never just themselves. We don’t just inherit theory, we inherit the anecdotes, gossip, and chatter that helped compose it—a tradition for whom the present continues to recompose. As of now, it is a living thing. No one can listen freed from history, from the frame. Analysts might gesture to this by collecting patients, grouping them diagnostically with the phrase “patients like this.” That’s what a composite case is explicitly meant to do. It covers the individual in a group to say, there’s no way to make sense of anything except via composing sense, and there is nothing but composite cases, even if we don’t intend to remix our patients and ourselves.

Psychoanalysis demonstrates the truth of two contrary assertions: knowledge doesn’t speak for itself without a theory to make sense of it, yet, more than any other framework of knowledge, psychoanalysis proves that knowledge does speak for itself by getting one heard. Once we can apply a type, know where to translate, where to press, we subsequently know how to listen better, yet those rubrics can also shut patients up and make analysts hard of hearing. From the very beginning, Freud had to form a stereotype out of his understandings of a singular case, applying it successively. This is what it is to make categories of the human mind. Even if the speaker doesn’t always know what they are saying, the saying of it works. The analyst, the great listening machine, provides the sense that was already there.

Infans means to be nonspeaking, but not to be silenced. Infants do communicate all the time. They have, some think, phantasy, aggression, wishes all their own. They grow and learn to speak and, moreover, to play. Children will tell us their reality, their fantasies, if only we listen. But when we listen for evidence, those children, like Anna Freud, come to understand their entire lives through their parents’ theories about them. The inheritance leaves little room, paradoxically, for true interpretation. In a similar vein, Marx writes, a “beginner who has learned a new language always translates it back into his mother tongue, but he assimilates the spirit of the new language and expresses himself freely in it only when he moves in it without recalling the old and when he forgets his native tongue.” Some of us never get a new language, we just reinherit the old, as if strange. Some of us learn the language of our home, once again.

To be the child of an analyst, then, is not to be a spectacular instance of that crossing of clinic and home, no more than it is to be a patient, made forever to oscillate between type and particular. To have a psychoanalytic theory, particularity had to be diminished in favor of use—a gesture toward universality. The fear of the child of psychoanalysis as a category, as a proxy for their parent’s madness, is a screen for the terror of becoming or being a patient. Anyone in analysis or thinking about analysis is, in effect, being and thinking as the “daughter” of analysts. We are all composite with its history, its patients, in family, on the couch. This is the meaning of transference.