Left-wing Melancholia

The Arab political subject

Nihal El AasarThere is no “non-Arab way out” of the Palestinian question. That was one of Ghassan Kanafani’s conclusions in “The Resistance and its Challenges: View of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (1970).” After the momentous loss of the 1967 Naksa and the advent of the Palestinian revolution, two competing ideas emerged regarding the Arab dimension of the struggle: Is Arab revolution and unity the route to the liberation of Palestine? Or does the liberation of Palestine need to come first to create the conditions for the sovereignty of Arab states and to rid the Arab world of imperialism? Either way, according to Kanafani, there is no doubt that the Arab dimension of the Palestinian struggle—and the mobilization of the Arab masses—is a critical step for any Arab national liberation project.

Kanafani saw the Palestinian revolution as one part of the broader Arab revolutionary struggles. This expanded the question of Palestine beyond today’s narrow framing—as solely Palestine vis-à-vis “Israel.” This limited frame is abstracted and displaced from Arab regional dynamics by separating not only the Palestinian masses from the broader Arab masses but also Palestinians from each other within Palestine. This approach seeks to isolate the Palestinian struggle and obscures the fact that the Arab working classes share a common political destiny. The challenges, in Kanafani’s eyes, were always tripartite: imperialism, Zionism, and reactionary Arab regimes—interconnected in a dialectical relationship. He demystified the link between Arab regimes and Arab masses, making it clear that the “present Arab reality” is one where “imperialism and its agents in [Arab] regimes prey upon the masses’ instincts towards national and class liberation on an equal footing.” Historically and contemporaneously, this is widely considered proverbial knowledge in much of the Arab world. Even without an inclination to certain ideologies, it is common to hear shopkeepers, taxi drivers, and others refer to Arab leaders as puppets and discuss ways to reclaim Palestine from the Zionists. Even instinctively, Arab streets can link a liberated Palestine to the future of the Arab world.

Since October, various considerations pertaining to the Arab world have rightfully been raised that need to be examined in depth: How has the wider Arab world reacted to this genocide, and why? What effects has the genocide had on the Arab masses? How have the reactions of the different Arab states—and the Arab public—impacted the increased and increasing brutality of the genocide? Finally, how has Al-Aqsa Flood and the ensuing onslaught on Gaza affected the levels of resistance within and against the Zionist state? These questions form the basis of my approach to this essay, though I do not claim to have fully answered them.

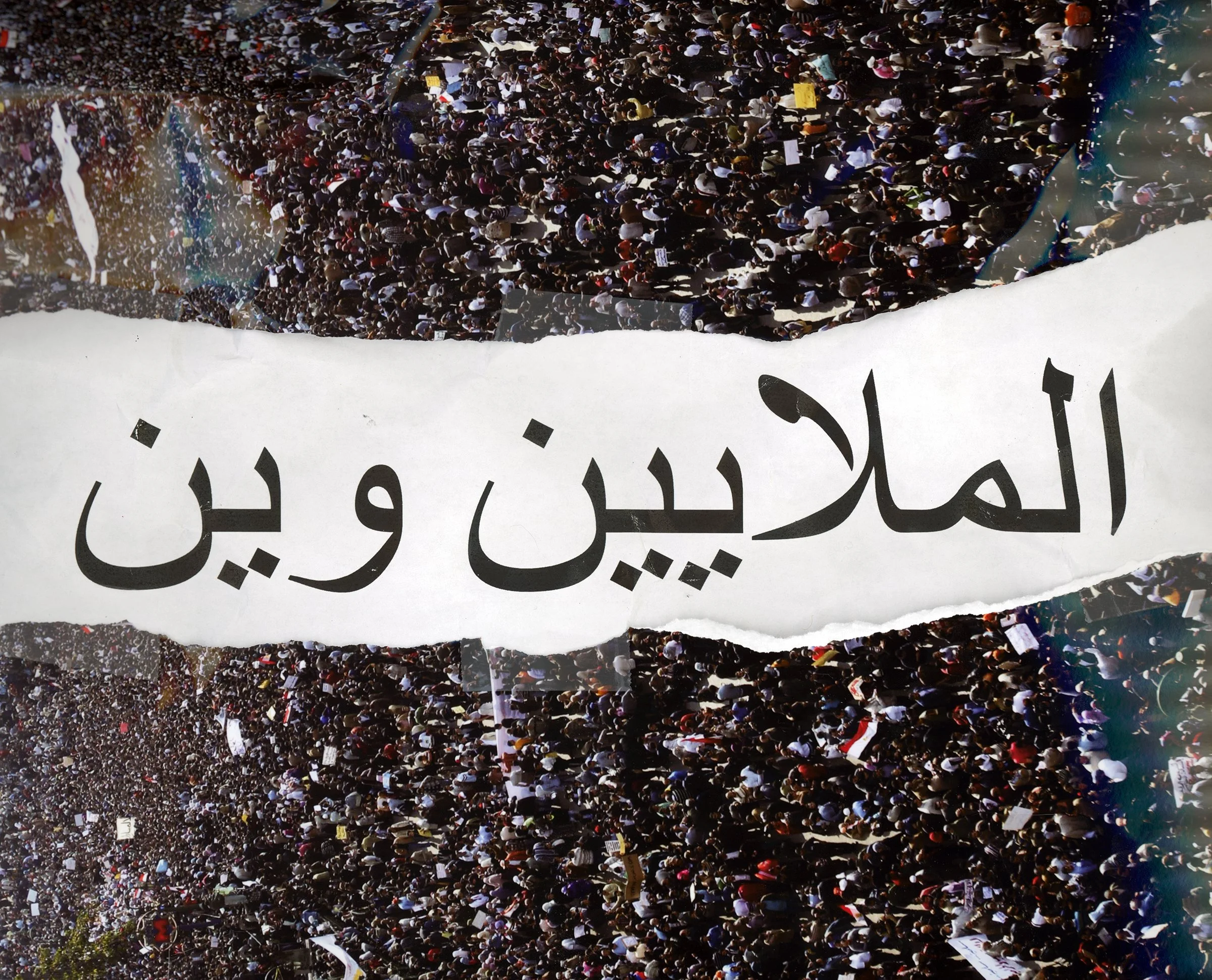

Rightfully so, there have been certain weighted expectations for the Arab masses to react more strongly and urgently to this genocide. Some have heeded the call; some have tried and failed. In reckoning with the responses—or lack thereof—of the Arab public, Palestinians and allies, friends and foes alike, have at some point over the past ten months asked, “Where are the Arabs?” This is a familiar refrain in the Arab world, heard on TV, in the streets, and even in music. One famous example is Lebanese singer Julia Boutros’s song وين الملايين or “Where Are the Millions?”—written by Libyan poet Ali Kilani.

Kanafani attempted to tackle the same conundrum. He argued that Arab reactionary regimes have weakened the national movement, but by failing to analyze the Arab world based on material conditions—rather than sentimentality and platitudes—the “strategic horizon” of the revolution had been obscured. He criticized the impulse of some Palestinian resistance factions who “sometimes blamed ‘the Arabs’ (just like that, without specifying) for a failure to liberate Palestine.” Instead, he offered a more nuanced assessment of the current conditions in the Arab world, analyzing the different ways the Arab world—regimes on the one side, and masses on the other—are positioned in relation to Palestine. In short, he specified how they are either complicit or not meeting the occasion.

“If the Arab national movement is partly responsible [for this state of affairs], it follows that imposing blame to the point of alienation means a failure to understand the nature of reality and its developments: that the petty-bourgeois Arab regimes proved incapable of ensuring conditions for the ripening of these Arab national movements, or to create an atmosphere practically conducive to the growth of other forces, because the majority of these regimes were not merely petty-bourgeois, but, further to this character—by the nature of their emergence and practice—also embodied military and policelike characteristics. Thus, their limited conception of partisanship and organisational action (including even the organisational action that it attempted to build to serve its own purposes) weakened the Arab patriotic parties and abandoned them to the battle when it reached a more advanced stage, with their formations strained, shaken and worn out in the extreme, both ideologically and organisationally.”

The Arab political subject is still grappling with domestic political conditions that affect their engagement with the question of Palestine. For Kanafani in this passage, however, there is no speculation about intentions or feelings. Rather, the focus is on a material analysis of conditions that inform political action.

*

In February this year, month four of the genocide, I read an article in the Lebanese newspaper Al-Akhbar that stuck with me. Titled “Death of the Arab Spring Subject” (موت إنسان الربيع العربي), it argued that the Arab political subject who participated in the Arab Spring must die to allow the subject of Al-Aqsa Flood to take their place. That is, the subject that relied on human rights organizations, NGOs, and Western institutions should be put to rest. In its place, a new political subject in the Arab world would emerge—one proposing methods of organization, resistance, and steadfastness, embodying a refusal to submit to defeat, despite siege, oppression, and conspiracies. Whether true or false, it made me want to seriously grapple with the question of the state of the Arab political subject before and after Israel's genocidal assault on Gaza.

One of the many ripple effects of October 7th was its complete rupture of the political landscape of the Arab world. The shockwaves disrupted the conditions of political defeat that had persisted since the movements across the Arab world, often referred to as the Arab Spring. Its reverberations were felt beyond the geographical confines of Palestine, where they exposed compounding contradictions in the Arab world and confronted us with our political subjectivity in a post-Arab Spring moment, jolting us out of its defeat-infused lulls.

In U.S-comprador states like Egypt and Jordan, the gap between reactionary regimes and the population was further accentuated, highlighting the disparity between state interests and the desires of the masses. Despite severe repression, people still flocked to the streets when the resistance called for major mobilizations. Jordanians marched to the Israeli embassy, and Egyptians broke into Tahrir Square for the first time in years. There, they modified the famous 2011 chant to “Bread, Freedom and an Arab Palestine,” resulting in the arrest of hundreds of people in both countries for protesting against Israel.

The insufficient response to the genocide on the border has led to a campaign of mass boycotts of Western products in the Arab world. This campaign represents a protest mobilization against both the ideological and material manifestations of U.S-led imperialism in the region, despite its longevity. In Alexandria, tensions heightened following the murder of two Israeli tourists in October 2023, an Israeli businessman in May 2024, and the murder of two Egyptian soldiers, who were reportedly killed in an exchange of fire with Israeli soldiers at the border. Discourse ensued where Israel was once again considered the enemy of the Arab nation—a further blow to the Egyptian state's long-standing stance on normalization since the 1978 Camp David Accords.

As clear as it was in the twentieth century, the fight is not simply about or within Gaza. Rather, it is felt across all Arab capitals—from Cairo to Amman to Damascus to Baghdad—and it is a cause for the masses of the region to organize around. The struggle for Palestine is a struggle for the future of the Arab region. The people of the region were aware of this in the twentieth century, and they remain aware of it now—despite decades-long efforts to enforce a top-down normalization.

Despite the above, the question of “where are the masses?” remains to be grappled with. As the Zionist state’s assault on Gaza has continued to intensify, we have seen some responses wane, especially those related to mass mobilizations. We could safely argue that the response of the Arab masses has not been sufficient to meet the political demands of the moment. If pro-Palestine and anti-Zionist sentiment remains for the most part strong in the region, how do we explain this paralysis? Is severe repression a satisfactory answer? If we understand the political subject as an individual with the political will to deliberately intervene in the course of history, how do we shift this subjectivity from being a bystander and witness to becoming an agent of history?

“If we understand the political subject as an individual with the political will to deliberately intervene in the course of history, how do we shift this subjectivity from being a bystander and witness to becoming an agent of history? “

To answer these questions, it is crucial to examine the recent history of the region and the context within which October 7th happened. The existing Arab political subject did not emerge at the dawn of October 7th; they are the product of the material conditions in which they exist. The past 12 years in the Arab world have been marked by counterrevolution, regional warfare, tens of thousands of Arabs killed, tens of thousands more detained, economic dependency, sanctions, Western intervention, and increasing autocracy and repression.

In the case of Egypt, while the fear of repression among the masses is justified, the extent of this social fear is a symptom of the failure to introduce serious counterhegemonic political and social forces. This has led to a kind of collective paralysis. Yet, this situation did not come from nowhere; it’s partly the result of intentional processes of depoliticization and political melancholy tied to the success of counter-revolutionary processes, which reversed any gains from the eighteen days of uprisings in Tahrir square. This has had disastrous effects on the potential for the masses in Egypt to view themselves as agents of history—agents of change—as well as a loss of political memory regarding organizing. Primed by the the NGO-ification of politics—due in large part to the outlawing of political organizing and the overreliance on rights-based organizations instead of grassroots organizing and political formations—an environment hostile to mass mobilization has developed. There are now young people in Egypt who have never participated in a political demonstration, voted in a student union, or filed a union motion. This is vastly different from the conditions that laid the groundwork for January 2011, which were forged through organizing during the second intifada, workers’ strikes, student organizing, and more.

This has led to political adventurism, confining political expression to disparate actions that single out actors, resulting in detainment and more repression. For example, in March, a sole individual in Egypt climbed atop a billboard and waved a Palestinian flag while calling Abdel Fattah al-Sisi a traitor was arrested. Similarly, two students who took the initiative to start a student movement for Palestine to coincide with the encampments across the United States were detained just days later.

The most significantly anti-Zionist populations in the Arab world were not sufficiently politically activated for the occasion, but it is not enough to simply wonder why; our task is to analyze the material conditions that have impeded this. After all, this same population invaded the Israeli embassy in September 2011, tearing down one of its outer walls, scaling the building to tear down the Israeli flag, resulting in over one thousand injuries and at least three deaths, and replacing it with Egyptian and Palestinian flags. During the Israeli assault of 2012, a delegation of almost five hundred Egyptians seized the political vacuum to enter the Gaza strip, becoming the single largest civilian group to do so since 1967. Was it not the student movement in Cairo during the War of Attrition that forced Anwar Sadat to launch the 1973 war? If it is not a lack of solidarity, then how do we explain the looming sense of political impotence that we are currently witnessing in Egypt.

What happens when a society has undergone, or still undergoing, a vicious all-encompassing counterrevolution? One need only look at the history of “failed” revolutionary projects—the inevitable decades of repressive corrections and counterrevolutions—to realize the extraordinary repression and erasure of political life for Egyptians since 2013. Closely followed and cheered on by people of conscience around the world, including Palestinians in Gaza, the January 2011 revolution was crushed by 2013. Whereas after Abdelfattah El Sisi’s popular coup initially sparked a mobilizing process, the gains made in political mobilization, strategizing, and developing political consciousness unraveled after 2013. Today’s Egypt serves as a stark example of the effects of political defeat: failed strategies resulting from a marriage between revolutionary defeat and continuously repressive counterrevolutionary processes.

*

Hannah Proctor’s Burn Out: The Emotional Experience of Political Defeat prompted this reflection on the current state of Egyptian politics. Not only does she draw from the Egyptian example several times, but her work also highlighted the importance of examining subjective experiences of defeat to complement material analyses. The chapters on “Melancholia” and “Nostalgia” specifically framed how I approach this question of Arab political subjectivity. Proctor builds on Enzo Traverso, Wendy Brown, and Walter Benjamin’s conceptions of melancholia. She argues that when melancholia is viewed merely as a mood or disposition, it fails to convey the material realities of defeat. Instead, the actual experience of political defeat is lived and experienced personally rather than epochally, as part of a specific moment in history. She contends that Traverso, for instance, focuses on the utopian imagination and the hollowing out of emancipatory promises of liberation, resulting from a perceived total loss in the past or failure to imagine a future, rather than viewing it as a material reality experienced daily as a result of collective struggle.

“Loss becomes the lost object. Marx and Engels’ specter haunting Europe came from the future, whereas the left-wing melancholic grieves for the loss of something that was never fully realized. And that ossified grief becomes a permanent political disposition.”

When we invoke the defeated or depoliticized Arab subjects, then, we must also think about the effects of defeat in after attempts to shape history—after the possibility of breaking with the status quo has been violently taken away. To this day, these subjects endure violent daily processes of disciplining and ordering that only serve to further entrench this defeat. We need to move beyond seeing January 2011 through a binary of defeat and victory—as a sudden epochal defeat—and instead understand it as a process of unraveling. This perspective prompts new political considerations that inform the current regional political arena. The condition of defeat, therefore, is not merely an affect but a process that is both inflicted on and experienced by the Egyptian political subject.

Seen through the lens of melancholia, defeat is not merely about affect. This change in political subjectivity is material—not merely intellectual, but experiential. In order to change this condition, prevent lingering feelings of melancholia, and reengage in political struggle, we have to grapple with defeat as a material reality, rather than as an epochal event. What, then, is the difference between learning from past struggles and melancholic romanticization? Proctor gives us the answer by differentiating between moribund nostalgia and political nostalgia, or left melancholy and mournful militancy. The former represents an unhealthy attachment to the past that impedes political action, while the latter involves an “engagement with revolutionary history that harnesses the energies of past experiences for the present.”

“Seen through the lens of melancholia, defeat is not merely about affect. This change in political subjectivity is material—not merely intellectual, but experiential.”

The melancholic condition is, of course, often mixed with nostalgia, resulting in an overly romanticized image of previous political hopes, particularly manifesting in an attachment to the mythical eighteen days in Tahrir. Egyptian political prisoner Alaa Abd El-Fattah wrote about this condition, stating, “Clinging to the mythic image of the square leads to neglect of revolutionary activity in the present. Contending with both hope (the square), and despair (the repression that came after), as part of a subjective transformation.” The Egyptian state is equally preoccupied, if not more, with the memorial status of January 2011, which regressed rapidly—from unprecedented obliteration of civil society, to having one of the worst political detainment records in the world, to a post-Paris Commune-like haussmannization and pedestrianization of roads, to moving government bodies and embassies to a new capital in the desert. This counterrevolution sought to erase 2011 from existence and prevent another one from occurring. If the regime’s disdain for 2011 is not clear enough from its actions, President Sisi often makes sure to evoke 2011 in speeches to comment on the disastrous consequences of people seeking to better their living conditions.

It is most unfortunate, then, that the Egyptian masses find themselves in a state of political subjectivity out of sync with the political demands of the moment. The political rupture opened in Gaza called for a new phase of resistance, but it found the Egyptian political subject stuck in a melancholic moment—attempting to heal from the past while the state is actively attempting to erase that past altogether. While Gaza’s attempt to break free ruptured an existing status quo on the border, Egyptians were living through an even worse reinstatement of the status quo ante from 2011. That is the predicament that characterizes the Egypt-Palestine situation in the post-October 7th moment: as the crack in the latter social order widens, the crack in the former is closing.

*

One cannot invoke the subject of defeat in the Arab world without mentioning the primary event that shaped the modern Middle East unlike any other: the 1967 loss to Israel by the Arab armies led by Egypt or Syria. This event is the central cause of left-wing melancholia in the Arab world and the benchmark against which all subsequent events are measured. As coined by Egyptian journalist Mohamed Hassanein Heikal, Gamal Abdel Nasser’s speech writer and confidant, the Naksa (the setback) frames the loss as part of an ongoing process as opposed to a final one. Egyptian historian Khaled Fahmy refers to it as the “continuous June loss” (هزيمة يونيو المستمرة) to illustrate that we are still living through its aftereffects.

The following is an excerpt from Lebanese writer and illustrator Lamia Ziadé memoir My Great Arab Melancholy, which illustrates the significance of the Naksa:

“June 5, 1967. Trauma, humiliation, disillusionment, loss of blood, loss of faith, distress, sadness, wreckage. The Middle East is annihilated, devastated. In just six hours, Israel has destroyed the entirety of the Egyptian air force on the ground. In Just five days, Sinai, Gaza, the West Bank, and Jerusalem are lost. Nasser is preparing to give a televised speech. The young officer in tears who was asked to type it hands it to him. Nasser reads it and makes a single modification. He removes the words “ready to assume my share of responsibility” and replaces it with “ready to assume all responsibility.” Egypt is glued to the television. He resigns. Egypt takes to the streets. Immediately, even before the speech has ended. All of Beirut, Baghdad, Damascus and Algiers too. “Nasser! Nasser!” Shouts, cries of despair, the crowd begs him to stay. He stays. He will die three years later, at the age of fifty-two. But really, he died on that day in June 1967, as the Arab world began to slide into a bottomless pit…”

The continuous and forced existence of “Israel” in the region signifies a permanent war not only against Palestinians but against Arab people as a whole. This, according to Lebanese academic Ali Kadri, is a cornerstone of the accumulation process in the Middle East. In an October 2023 interview, Kadri argues that the extraction of human life is the first step in extractive economies like those in the Third World. The price of extracting these resources has been particularly high for us in the Middle East. The presence of the Zionist entity in the region represents one of the highest costs, playing a functional role in securing imperialist interests in the region.

“The Arab left was hit with left-wing melancholy three decades before the Western left, as signified by the fall of the Soviet Union and the tearing down of the Berlin wall.”

The 1967 loss was integral to this. Only after 1967 did the United States realize the value of Israel’s presence in the region. The United States then intensified its support for Israel, both financially and militarily. While the United States was engaged in its war against the Vietnamese people, Israel was able to conduct its dirty Cold War work for it in another part of the world. As the famous Joe Biden saying goes, if Israel didn’t exist, the United States would have had to create one. Israel became a primary vehicle for combating Soviet influence and nascent Third Worldist non-alignment and Tricontinentalism in the Arab World. Not only did Israel defeat the most powerful army in the Middle East, but this defeat also delegitimized and defeated the dual project of Pan-Arabism and Arab socialism, as embodied by Nasser and other leftist Arab radical movements. These movements were ultimately seen as having failed to achieve victory and Arab liberation, leading to a loss of sovereignty for major states in the region. Theodr Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, even described the Zionist state as a bulwark around “Arab barbarism.”

Kadri argued that the condition of defeat experienced by the Arab masses is a material reality of United States-led imperialism in the region. He rightfully pointed out that, if we were to extrapolate the contemporary history of the region, there is no stage in which our people were not repeatedly attacked. Kadri goes further to assert that instilling a sense of defeat in the Arab masses was integral to the post-Soviet order imposed by capital in the Third World. If the people in the region were not continuously beaten and defeated, then the capitalist machine propelled by imperialism would not be able to function.

“In the Arab world, to subvert melancholy without subverting the entrenched Israeli occupation and the continued Euro-American domination is to miss the mark and appropriate attention away from the underlying injustices of which melancholy is the product.”

In his book Melancholy Acts: Defeat and Cultural Critique in the Arab World, academic Nouri Gana makes the striking observation that the Arab left was hit with left-wing melancholy three decades before the Western left, as signified by the fall of the Soviet Union and the tearing down of the Berlin wall. This melancholy was compounded by the fact that the radical Arab left movements were very much still nascent and militarized before they were suddenly ejected out of history by the 1967 loss. This was a leftist social-political formation, where national liberation was inseparably intertwined with socialist ideas, meant that the loss of the former led to the inevitable fall of the latter. Gana argues that melancholy in the Arab world is primarily the product of the colonial relations that underpin it and its alignment with global imperialism.

“It is as if the defeat had catapulted or expelled Arabs out of history at the very moment when they were re-entering it with the decolonial ideology of Arab nationalism and the successful anticolonial movements that had become exemplars of Third-Worldist and non-alignment imagination . . . the 1967 defeat decimated the conceptual foundation of the promissory project of a decolonized, united and emancipated Arab nation and laid the basis for the disunited dictatorships and compromised national sovereignties of most Arab countries… the social and psychological destruction of colonial violence would soon be reenacted internally and under different forms, ranging from recurring coups, riots, and insurrections to brutal power struggles, political assassinations, massacres and lengthy civil wars.”

*

In the form of the reactionary Gulf oil monarchies and their rentier economies, which many Arab nations rely on, the retrenchment of financial capitalism is arguably one of the many aftereffects of 1967. The Camp David and Oslo accords are further manifestations of the same post-67 processes. The failure of the Arab left then—and its continued failure now to transform society—must be understood in relation to the presence of the settler-colony, which requires a combination of imperialism and supportive Arab regimes to ensure its survival. After all, if Israel did not exist, there would be no similar need for imperialists to prop up and support authoritarian governments on its borders. This creates a vicious cycle: a global system of imperialism propped up by its economic and military legs, finance capitalism that erodes the economic sovereignty of Arab states and entrenches the defeat of their working masses, and the existence of military bases to ensure the safety of its settler colony and its interests. In comprador states like Egypt and Jordan, the United States leverages debt through its financial institutions to ensure subservience to global markets, while it leverages sanctions as a form of warfare against more recalcitrant countries, such as the Axis of Resistance.

Under different forms of discipline, both types of states remain subjects of imperialism. The former can be evidence by the U.S. releasing the full military aid allotment of USD 1.3 billion, with Blinken citing “Gaza help” explicitly as the reason for the full allotment of aid, despite withholding some of the aid in previous years due to concerns about Egypt’s human rights record and the high number of political prisoners. The Egyptian regime’s repressive treatment of its citizens have remained the same or even gotten worse since last year when some of the aid was withheld, the only thing that changed this year was its role in aiding U.S. interests in the region during the assault on Gaza and repressing its 100 million strong largely pro-Palestine population rather than use them to exert pressure on the U.S. and Israel as had been done by previous Egyptian presidents for example.

However, in the latter countries, U.S strategy towards them allows the masses to express their pro-Palestine sentiments more openly, because the state is not focused on disciplining them over U.S. defiance. This only frees up these states to be openly hostile against U.S. interests in the region, with its proxy, “Israel,” as this primary manifestation. In both cases, it is not a question of the leaders' intentions—what the King of Jordan, El-Sisi, or Hassan Nassrallah hold dear to their hearts—but rather where they fall in relation to U.S. imperialism in the region and where their national interests lie.

To clarify this situation, let’s consider Nidal Khalaf’s argument in “Death of the Arab Spring Subject”: that October 7th has created a new kind of Arab political subjectivity. What kind of subject has it awakened?

Clearly, the interests of the ruling classes in various Arab client states are closely connected to United States-led imperial capital, illustrating their relationships with the West, other Arab countries, and their own populations. This relationship developed historically through relentless proxy warfare and direct intervention, from Libya to Lebanon to Egypt to Iraq, defeating developmentalist projects and widening class divisions. “Israel” has continued to be a clear existential threat, largely responsible for the destruction of the Arab East outside of Palestine. Its destructive effects are felt across the region: in Lebanon, which it invaded in 1982 and whose airspace it violates more than two thousand times a year (prior to October 7th), and with which it has been at war with since October 8th, martyring over five hundred people in the South; in Syria and Iraq, previously two of the most sovereign states in the Arab world, both of which have suffered greatly; and in Egypt, which has been neutralized as a threat. It is engaged in modern day warmongering toward Iran and Yemen, conducting assassinations in Arab capitals and dragging the world into regional conflict. And of course, the most recent terrorist style detonations of pagers and equipment with lithium batteries in Lebanon which has resulted in thousands of injuries and nine deaths (so far), including children. As historian Ussama Makdisi puts it, “Israel" is a state and society that is “committed to exterminating the brutes,” representing a persistent threat of war, death, and destruction against Arabs.

“This resistance challenges the status quo of defeat and takes up the fight for the future of the Arab world at the sharpest edge of U.S. imperialism.”

Occurring when it did, Al-Aqsa Flood not only deepened the contradictions between the reactionary states of the region and their people but also between Arab states that fall on either side of U.S. imperialism. This shattered, at the very least, the manifestations of defeat on the military front. Militarily, it demonstrated that some of the most disadvantaged people in the region—and the world—can stand up to one of the most funded and supported armies, despite being besieged, sanctioned, and monitored. Politically, the operation clearly resisted and positioned itself outside the framework of the U.S./Saudi normalization efforts. This, in turn, threatens the alliance between the economic and military aspects of imperialism and the reactionary Arab regimes, providing alternative political horizons.

One illustrative example of this political effect is a shocking January 2024 speech by Sisi, in which he addressed Egypt's economic crisis and the Egyptians’ grievances about record price hikes for staple items. He compared Egypt’s conditions to Gaza, saying, “God sent us a living example of people on the border who we cannot even send subsistence food items to,” using this comparison to suggest that Egyptians should endure their hunger because it could be worse. This reference is particularly egregious given the state’s role in managing the Rafah border. The underlying message of the speech was to instil fear and discourage the masses from defying the status quo and seeking better conditions. For Sisi, October 7th represents a threat because it stood as a reminder for the masses of Egypt that their brethren in Gaza sought to disrupt the status quo and suggests that they, too, could potentially do the same. In the same speech, he sought to remind regular Egyptians of the potential consequences of such actions, while once again blaming January 2011 for the collapse of the Egyptian economy.

As it stands in Egypt, protesting in support of Palestine has been banned, and waving the Palestinian flag at a football event can get you arrested. The brutality of the crackdown is directly linked to the proximity of the genocide in Gaza. Reactionary states have responded by intensifying their oppression. They are very much aware that their populations might draw inspiration from those resisting the status quo on the border. This resistance challenges the status quo of defeat and takes up the fight for the future of the Arab world at the sharpest edge of U.S. imperialism. The strong response is intended to discourage any resistance or search for better living conditions among the Arab masses. The imperialist world order depends on this suppression for its processes of accumulation and capital flow, while client regimes rely on it for their longevity and legitimacy through Western support.

Kanafani’s analysis in 1972 remains true today:

“The Arab countries surrounding Palestine were playing two conflicting roles. On the one hand, the Pan-Arab mass movement was serving as a catalyst for the revolutionary spirit of the Palestinian masses. On the other hand, the established regimes in these Arab countries were doing everything in their power to help curb and undermine the Palestinian mass movement. The sharpening conflict in Palestine threatened to contribute to the development of the struggle in these countries in the direction of greater violence, creating a revolutionary potential that their respective ruling classes could not afford to overlook.”

Though it did not instantaneously lead to the required mass mobilizations, the aftermath of October has still resulted in various shifts within the Arab world. The intellectual relationship with the West has been broken, and trust in international institutions and liberal frameworks has been significantly shaken. Several NGOs and rights-based organizations have had their funding cut from German institutions as a result of their support for Palestine post October 7th. This has created a vacuum different from the one left in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. The appeal of the Axis of Resistance and multipolarity has expanded to include circles that would have previously opposed it, as they pragmatically view it as a way out of the wreckage.

The Palestinian cause, while being an integral facet of any struggle for liberation or radical ideology in the Arab world, has experienced ebbs and flows. However, due to Israel’s expansionist nature as an imperialist settler colony, the promised dividends of peace through capitulation have never materialized. Yet, it remains clear to the Arab masses who their natural enemy is, as it impedes their progress.

It is not a coincidence but a choice for Al-Aqsa Flood to fall on the 50th anniversary of the Arab War on Israel in 1973. The Palestinian national war of liberation consciously or unconsciously builds on the accumulated political memories of previous Arab struggle and projects itself toward a future of liberating the Arab homeland from Zionism. The resistance, aware of the reality of unfinished political processes, did not reject the past a priori but combined it with the different material conditions of the present, thereby revealing the cumulative character of history.

For Rosa Luxembourg, defeat was always necessary to achieve final victory. Similar to the Hezbollah’s 2006 military victory against Israel, this moment must be treated as part of a cumulative effort that will lead to further sharpening of contradictions and, eventually, to liberation. It is now the task of the Arab masses to grapple and move through the melancholy—and the defeat—and to rise up to the political moment.