Off the Couch

lights, camera, psychoanalysis

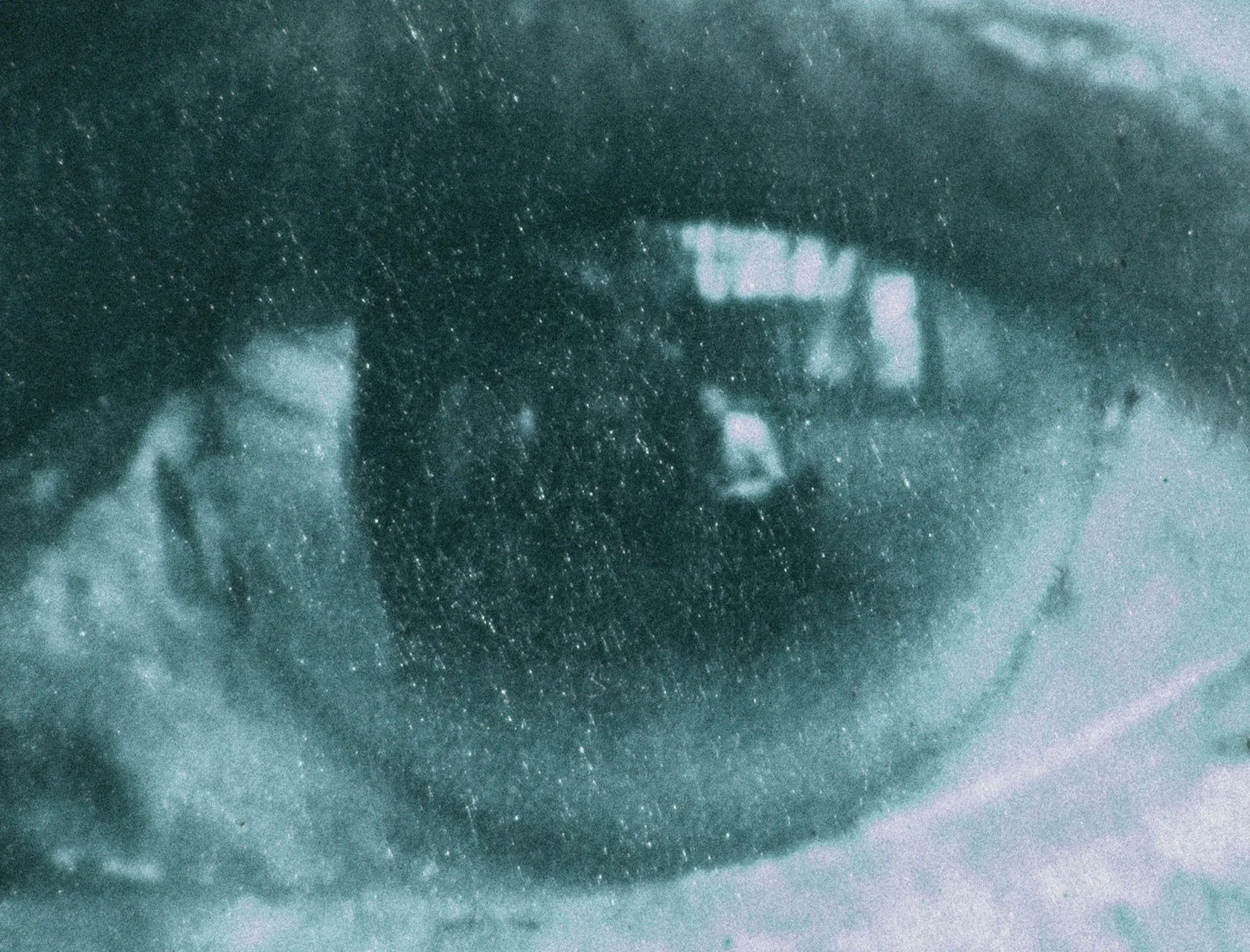

Federico PerelmuterA dark leather couch faces forward; behind it, a matching leather chair. A sleek metallic lamp droops over two people, one seated, one lying down. Both face the same way. A psychoanalyst’s office? Well, almost: the wash of industrial, shadow-proof lighting and bright background necessary for live television broadcasting dilute the psychoanalytic clinic’s typically somber and intimate ambience. Gabriel Rolón, undoubtedly Argentina’s most famous psychoanalyst, sits in the chair with a clipboard but no pencil or pen, and in each hour-long episode, a rotating cast of Argentine celebrities subject themselves to his trained analytic ear in front of a battalion of TV cameras. Crass, but effective. Don’t mind the studio audience: free associate!

These scenes are commonplace in Argentine media, where psychoanalysts like Rolón turn the analytic method into entertainment. A practicing analyst as well, Rolón has been working in the public eye since the 90s, when he featured in the popular radio show La venganza será terrible [Vengeance Will Be Terrible] and won a place for himself on TV in the early ‘00s. His shows on the small screen, like the prime time Terapia (única sesión) [Therapy (Single Session)] or Diván para todos [A Couch for All], featured iterations of the scene described above, as did the many radio shows he has led over the last quarter century. His fame ascended most markedly with the release, in 2007, of Historias de diván [Couch Stories], a book that has sold hundreds of thousands of copies through dozens of editions in a country where bestsellers will only sell a couple thousand. In 2013, it was adapted for television, and the ten or so books Rolón has published since—further anthologies of cases, as well as books on love, grief, communication, and passion among other subjects—reliably top the sales charts for months post-publication. The explanation for such a unique figure is often found in Argentina’s remarkable psychoanalytic culture.

It's almost trite to say, but true nevertheless: psychoanalysis is an Argentine obsession, and especially so in Buenos Aires, where analysts have their own unofficial neighborhood—Villa Freud—and cluster in exorbitant numbers: over 200 per 100,000 inhabitants for Argentina, and, per one 2013 study, at least 1200 per 100,000 in Buenos Aires, 12 times more than the runner-up. The fascination that visiting Europeans and Americans feel for Buenos Aires’ psychotherapeutic culture has even evolved into a subgenre of piece, remarking upon Porteñxs’ (Buenos Aires inhabitants) passion for therapy in the context of Argentina’s tragic history. These articles follow a comfortable sequence, fetishizing the country’s refined psychoanalytic culture: remark upon the statistics I cited above, affirm that Argentina was once among the wealthiest countries in the world and is now an economic house of cards with a history of political instability, wonder if this might explain the statistics, and invite a psychologist and an academic who attempt to provide a more cogent answer. Their answer might extend into psychoanalysis’ expansion in the country, or some speculative analysis of “Argentine culture,” its obsession with European trends in the 20th century or as opposed to “American” something or other. Scholars of psychoanalytic history and psychoanalysts themselves have explained the phenomenon, but their non-sensationalist responses—combining economic, political, social, and cultural factors—are rarely broadcast. Media personalities like Rolón, trained in the field and thus are familiar with its history, nevertheless opt for the culturalist explanation, connecting psychoanalysis’ popularity with Argentina’s 20th and 21st century immiseration.

Given his penchants, it comes as no surprise that psychoanalysts are not buying Rolón’s books in droves. Rolón’s audience overlaps with the self-help crowd, demonstrating his commitment to making the Freudian method accessible—after all, books and cable are cheaper than therapy—and willingness to blend psychoanalysis with other bodies of knowledge, though he insists on calling himself a psychoanalyst. Rolón detractors abound, even though every metric suggests that audiences love Rolón, and he seems to believe that his peers hold him in high regard, with awards flooding in from universities and professional associations. When I asked actual and future psychotherapists for their thoughts on Rolón, their responses were fairly consistent. For example, Carolina, a senior psychology student at the University of Belgrano, said that she found Historias de diván inspiring when she was considering the course of study in her teenage years, but that as she’s grown more knowledgeable about psychology and psychoanalytic practice, her esteem for him plummeted. For her, Rolón is egocentric and more interested in displaying his own knowledge than in helping his patients. Negative opinions have remained consistent across every interviewed psychoanalyst, mine included. In fact, good luck mentioning him to one without eliciting a rather displeased chortle.

It’s not unsurprising that specialists would think less of someone who does public-facing work that shamelessly misrepresents the discipline in search of individual success. The strength with which they voice their rejection also suggests that Rolón’s image is not simply irritating but symptomatic, if you will, of a cheapened analytic discourse separated from practice: psychoanalysis not as therapy but as entertainment. Rolón, together with his peers who work in mass media psychoanalysis—like Luciano Lutereau and Darío Sztanszrajber—have earned the disdain of an Argentine psychoanalytic community deeply concerned with preserving its integrity by giving ammunition to psychoanalysis’ detractors. For them, mentioning Herr Freud in the media is itself doing a social good, as if the central goal were explaining the Oedipus complex to audiences instead of treating them. Psychoanalysis cum performance, with a couple patients to the side just to sell it.

Rolón is an undeniable product of a century of struggle to grow a psychoanalytic culture through persecution and censorship. Instead of preserving that legacy of commitment to the care of mental health, from public psychiatric hospitals to revolutionary organizations and parallel universities, Rolón named himself Psychoanalyst-In-Chief for explaining celebrities’ love lives on TV. How did Argentine psychoanalysis get from the revolution to here?

*

Though psychology and psychoanalysis are not the same, they overlap almost entirely in contemporary Argentina. Whereas psychoanalysis arrived, slowly, starting in the 1910s, psychology only emerged in force in the 1950s. Contemporarily, psychoanalysis is the main theoretical current in the country, with 44% of psychotherapists practicing it, as opposed to around 30% offering CBT-related therapy, according to another study. As Mariano Ben Plotkin shows in his classic history of 20th century Argentine “psychoanalytic culture,” Freud in the Pampas (2001), psychiatrists were the first to acknowledge psychoanalysis, though they remained committed to positivism and degeneracy theory as poor European immigrants continued to stream into Argentina and were overrepresented in mental hospitals. Positivism’s hold weakened as the theory became increasingly associated with the “materialist empire of the North,” and a new Latin Americanism took hold, which, together with the intellectual upheavals that followed World War I, crystallized psychiatry’s need for theoretical renovation. José Ingenieros, the most eminent Argentine psychiatrist-philosopher of the early 20th century, proved increasingly receptive to some of Freud’s ideas, though never unreservedly. Psychoanalysis was, even when rejected, associated with modernity, and acknowledged as an important current of thought; until the 1940s, Plotkin suggests, psychoanalysis was “a tool that could be added to and sometimes combined with more traditional techniques and theories.”

The lack of a central orthodoxy in the early years, explained partly by the lack of IPA-trained (International Psychoanalytic Association) psychoanalysts in Argentina, made psychoanalysis more a subject of interest than a particularly partisan or rigorous corpus, and both left- and right-wing psychiatrists picked it up. Left-leaning psychiatrists like Gregorio Bermann, an idiosyncratic communist, and Emilio Pizarro Crespo, who attempted a synthesis of Marx and Freud in the 1930s, shared editorial boards with right-wing figures like Juan Ramón Beltrán, one of the first self-described psychoanalysts in the country, who combined Freud’s ideas with degeneration theory and criminological thinking. As interest expanded in the late 1930s, some aspirants, like Dr. Celes Cárcamo, traveled to Europe for “proper” psychoanalytic training with the IPA, and returned to practice locally. In 1942, IPA-trained exiled Spanish psychoanalyst Ángel Garma, Cárcamo, and a group of “young, progressive doctors who were only marginally connected to the psychiatric establishment” founded the APA (Argentine Psychoanalytic Association) and were quickly accepted into the IPA. Chief among these aspiring analysts were Arnaldo Rascovsky, a pediatrician, Enrique Pichon Rivière, a promising young psychiatrist, and their wives, Matilde Wenceblatt and Arminda Aberastury. The APA was initially open to those lacking university education, like Wenceblatt and Aberastury, though they eventually began enforcing the IPA’s strict membership guidelines to regulate who could practice psychoanalysis. A 1954 state regulation requiring an MD to practice psychotherapy confirmed APA hegemony, which remained unchallenged until the 1970s. Because most analysts in Argentina were locals, psychoanalysis was not especially associated with exotic foreignness or with Judaism, as it was in the US.

Theoretically, Argentine psychoanalysts in the 1940s and 50s were strongly opposed to any currents associated with the US, preferring French and, later, English currents. For the mainstream, Melanie Klein became a sort of intellectual godmother, particularly as child and family psychoanalysis spread (spearheaded by Wenceblatt and Aberastury). By the end of World War II, a small cluster of communist psychiatrists were also wrestling with psychoanalysis, following the French Communist Party’s denouncement of psychoanalysis (antirevolutionary, American, Jewish, and bourgeois!) in favor of Pavlovian theory. Their Argentine counterparts followed suit, though not for long, returning to psychoanalysis after reflexology proved insufficient. The so-called “New Psychiatry,” emergent in the late 1950s, transformed the asylum model and insisted on a broader, systematic understanding of mental illness and treatment; in this context, “psychoanalysis began to be seen as a valid psychiatric technique,” Plotkin writes, present in public psychiatric hospitals.

The middle class, psychoanalysis’ perennial subject, was expanding rapidly with Juan Domingo Perón’s populist political program, which accelerated the development of consumer culture in the country. Perón came to power in 1945 after a landmark election, and a coup ousted him a decade later. Despite his well-known beneficence towards workers, Perón’s authoritarian streak led to disruptions of independent university life, quiescing intellectual life in the country and forcing psychoanalysts towards parallel institutions of study. The coup that exiled him in 1955 and proscribed Peronism, the country’s majority political force, inaugurated an era of political instability that lasted, with brief interludes, until the 1980s. Thus, Plotkin suggests, the newly affluent and technocratic middle class found that “as politics was not…an arena in which social conflict could be regulated and channeled, some people preferred to turn inward to seek explanations that traditional concepts did not provide.” Psychology, which developed as a discipline after psychoanalysis was established, became a major at universities across the country in the late 1950s, reflecting the educated classes’ growing interest in the field. Most available and sufficiently prepared psychology professors were trained in psychoanalysis, leading to its dominance among faculty and in curricula. Lacking an MD, alas, psychologists could not legally practice psychotherapy, brewing ever-growing resentment of the APA.

In the decade after Perón, from the mid 1950s until 1966 when another more violent dictatorship came into power, intellectual life flourished, including a newfound interest in Sartre and other French philosophy that further spread psychoanalysis among the Left. Psychologists, more likely to lean left-wards than APA members, were an important part of the psychiatric workforce, even without legal permission to practice psychotherapy. Psychoanalysis slowly left behind its cliquish, esoteric origins among elites, and became receptive to grandiose political visions as it fused with psychiatry in public mental hospitals during the 50s. Psychoanalytic therapy—particularly group therapy, which remains unusually popular in Argentina—became available at most psychiatric clinics as the asylum model finally vanished. Pioneered in Argentina by Enrique Pichon Rivière in the late 1940s—though this got him fired by Peronist authorities—the practice spread quickly in the 1950s. As Plotkin puts it, the practice “dramatically expanded the clientele for psychoanalytically oriented therapies…to working-class men and women” who could now find options for therapy at no charge. The method was used not only to treat mental illness but also more commonplace neuroses, and psychology graduates were allowed to practice in collaboration with M.D.’s, redefining “the scope and professional status of psychoanalysis” and bringing it closer to the social sciences while expanding its cast of active practitioners. By the late 1950s, psychoanalysis was a signal concern of the intellectual class. No longer available exclusively to wealthy intellectuals, the role of the psychoanalyst changed as the clinic brought into view new class-based political conflicts, mainly between mostly working-class Peronist patients and historically wealthy anti-Peronist analysts. Psychoanalysis thus became embedded within a broader political project: for some, liberal and conciliatory, for others, potentially revolutionary.

How did Argentine psychoanalysis get from the revolution to here?

Polarization signed the 1960s: in 1966, the dictator Onganía sent the military into the country’s universities. Leading scholars went into exile or unemployment, and political violence replaced the intellectual fervor of the prior decade. Psychologists, still barred from having private psychotherapeutic practices, felt themselves closer to intellectuals than health professionals. They were very receptive when, in the 1960s, leftist semiotician and critic Oscar Masotta introduced Lacan to Argentina. Masotta lacked any clinical inclination, but his influence grew and in the 1970s he founded the Freudian School of Buenos Aires (a tongue-in-cheek reference to Lacan’s École Freudienne de Paris). The APA, of course, was not particularly appreciative of the competing organization. In this context, APA members grew increasingly at odds regarding the political possibilities of psychoanalysis: the most radical believed that psychoanalysis could and should serve a revolutionary purpose, to heighten and sharpen people’s radical commitments. In 1971, two groups of psychoanalysts—Plataforma [Platform] and Documento [Document]—split publicly and collectively with the APA, the first ever instance of politically motivated secession from the IPA or one of its affiliates. Psychoanalysis had become by this point an essential, political frame, inextricable from a broader Left-wing political project.

When the last and most horrific dictatorship seized power in 1976, alongside a program of systematic disappearance and murder of leftists, trade unionists, and others, as well as censorship and the suppression of most civil liberties, psychoanalytic organizations like the APA were marginalized, though Plotkin suggests that whether psychoanalysts were disproportionately persecuted is unclear. Undoubtedly, the military and its accomplices believed that “mental health centers had been turned into centers of subversive indoctrination,” and they persecuted and disappeared politically engaged psychoanalysts. The APBA (Association of Psychologists of Buenos Aires), a more politically inclined organization, was persecuted, including through the disappearance of its then-president, Beatriz Perosio. The APA, meanwhile, mostly abstracted from politics to avoid such repercussions. The utopian vision of psychoanalysis as a politically radical, aspiringly liberatory project was, as with most Left activism, disarticulated by the dictatorship’s program of terror and brutality.

Democracy returned in 1983, and the historiographic trail mostly vanishes at that point: few scholars have attended to the intellectual or social history of Argentine psychology, which is to say psychoanalysis, after democracy returned. Important changes transpired: the law requiring an MD to practice psychotherapy was struck down in 1985, though it hadn’t been enforced for some time, and the APA opened its membership to psychologists and loosened its regulations (a similar transformation took place in the United States at the same time). Lacanianism became dominant, or at least highly prevalent, to the point that Jacques-Alain Miller, Lacan’s heir and son-in-law, makes yearly visits to Buenos Aires. Institutional rebuilding has taken place, as has a market-oriented reform of university curricula brought about by heightened state regulation; private universities became, starting in the 90s, increasingly powerful, decentralizing traditional public institutions. In 2012, a law defined mental healthcare as a human right, furthering diffusion of always-psychoanalytic psychotherapy. As it did elsewhere in the world, self-help became an undeniable force, selling countless books every year and exerting tremendous influence on the public sphere.

*

Gabriel Rolón, prominent by the mid-90s, was part of that first generation of psychologists to have full, uninhibited participation in the psychoanalytic establishment. He graduated from the University of Buenos Aires in the mid-80s, as democracy returned and the public sphere reemerged, and became the most prominent psychoanalyst of his age group. Psychologists’ inclusion in the establishment garnered some backlash from its most traditionalist members, who saw the APA’s high standards eroded by the lax guidelines of university psychology programs. Undeniably, the APA was broadening its scope to leave behind an outmoded elitism and acknowledge the mountains of interest in psychoanalysis. It remains the most prestigious association for psychologists, but APA liturgy has widened to include a broader range of approaches and backgrounds. Membership, nowadays, is mostly contingent on passing a long and difficult exam. Rolón’s relatively idiosyncratic mishmash of Lacan and Freud—and the occasional Melanie Klein reference for good measure—resembles, to some degree, the approach of most psychologists, and is similarly a product of Argentina’s psychoanalytic cultural history.

Though psychoanalysts are famously reserved about their practice, Rolón inherited a long tradition of public-facing and mass psychoanalytic culture in Argentina. Psychoanalysis did not reach the country through the artistic avant-garde, as it spread in Europe and the US, but the doctors and other professionals who brought Freud into the country’s intellectual landscape worked to ensure its careful and thoughtful dissemination. Simultaneously, the left edited mass-market, low-cost translations of Freud and other intellectual luminaries as part of a public education project that scholar and psychoanalyst Hugo Vezzetti described as a “mass plebeian leftism.”

The “psychoanalyst’s office” first appeared as a twist on the traditional advice column in Jornada, a short-lived newspaper in the early 1930s, and lasted less than a year. Women—the main market for the section—would mail in their problems and dreams, and “Freudiano” [Freudian] would analyze these by applying theory with notable rigor, never making recommendations but offering insights. As psychoanalytic culture grew, dispatches from the “psychoanalyst’s office” became a fixture of Argentine print media, though rarely with comparable theoretical solidity. When Viva Cien Años magazine opened a psychoanalysis section in the 1940s, their expert became an all-knowing advisor expostulating conservatively in hopes of preserving marriages and families intact above all else: a psychoanalysis of pacification, a defense of gender roles and structures, arguably similar to Rolón’s. The dynamic was simple: readers, mostly women until this day, wrote in with reports of dreams and problems that the anonymous columnist interpreted. By the 1950s, many magazines carried a similar feature. The writers behind these columns, though anonymous, were often intellectual luminaries like Gino Germani, father of Argentine sociology, Enrique Butelman, founder of Argentina’s most prestigious psychoanalytic publishing house, and Grete Stern, a renowned photographer who assembled famous montages, visual interpretations of the dreams being analyzed. Peruvian poet and intellectual Alberto Hidalgo pseudonymously edited and wrote “Freud al alcance de todos,” an influential mass-market collection of rewritings of Freud’s ouvre. Though Argentina’s mass media was often hemmed in by censorship, psychoanalytic discourse became inseparable from the magazine form throughout the 20th century, and soon psychoanalysts were being called in to “analyze” politicians and public figures. During the explosion of cultural life in the 1960s, and again in the post-dictatorship period, the psychoanalytic lens remained central. For most of them, media work paid the bills and was not itself a career.

Meanwhile, Rolón, who built his celebrity on similar work, carried the storied, familiar form, first to radio and, later, to television. Conservative in style, quiet, and restrained, Rolón’s appearances were never innovative, but his sobriety gave him an air of haughty, intellectual respectability. He played it straight while surrounded by the erudite provocateurs of Argentina’s “shock jock” radio MC generation, like Alejandro Dolina. Books, alas, remain essential for assembling the persona of a respectable public intellectual, and Rolón’s followed the logic of his radio appearances, mostly dealing with patients’ experiences and drawing self-help style ‘lessons’ from them. No simple entertainment, Rolón was serious stuff, or so he claimed. His reception suggests otherwise: few intellectuals or psychoanalysts would regard him as an eminence or someone ‘worth reading’, unlike predecessors like Butelman, Germani, or Stern.

Historias de diván, Rolón’s most famous and first book, is a collection of cases—eight in the first edition, nine in a subsequent edition, ten in the latest. Per the subtitle, “diez relatos de vida” [ten life stories], the book presents the true stories of lives reshaped by Rolón’s analytic intervention and which, seemingly, reshaped his own worldview and therapeutic practice. They stand opposed to Freud’s paradigmatic case studies, which focused on the method and process of analysis. Even if the patient is the titular protagonist (“Dora,” “Little Hans”) and center of attention, Freud’s objective was always to demonstrate the operations of psychoanalytic therapy, to unpack how certain situations are to be resolved and reflect on errors and successes, to extrapolate new theory. Needless to say, Rolón is no theorist. His cases serve turn patients into exhibits and near-truisms, their stories his to exploit. He cites Freud and Lacan occasionally—though no others—and mostly limits himself to overly simplistic, abstract accounts of psychoanalysis’ power and the “life lessons” it teaches. Unlike conventional self-help discourses, which promise wellness in idiosyncratic, anti-academic terms, Rolón’s reliance on Argentina’s illustrious psychoanalytic history, of which Rolón is part and parcel, grants his interest in cheap cliché a veneer of respectability.

Rolón also avows his commitment to spreading the gospel of psychoanalysis, a somewhat anachronistic claim that explicitly connects him to Freudiano and the other disseminators who were active while psychoanalysis was utterly marginal. In fact, Mexican anthropologist Xochitl Marsilli-Vargas’ recently published Genres of Listening: An Ethnography of Psychoanalysis essentially rests on the idea that all citizens of Buenos Aires are completely awash in psychoanalytic ideas (of listening especially, but more broadly too), emphasizing the slight absurdity of Rolón’s claim. Marsilli-Vargas’ book lacks some sensitivity to class dynamics and falls into a somewhat flimsy universalism—a consequence of her perceptiveness and ambition—but is alive to Rolón’s reliance on psychoanalysis’ diffusion. He is, above all, an expert invoker of stereotypes: Marsilli-Vargas affirms Rolón’s undoubted expertise as an analyst, emphasizing his small role within a broader media ecology of psychoanalysis. For her, Rolón is “an expert listener,” “a very savvy communicator” who offers a “bravura psychoanalytic performance” during a television appearance. But in writing, Rolón’s alleged commitment to spreading what he calls “the sacred flame of passion for Psychoanalysis [sic]” disintegrates into sentimental truism, and becomes a self-confirming mythology, less a therapeutic project or a theory of the soul than a smattering of generic affirmations somehow meant to “inspire” his audience.

Rolón’s popularity ballooned as self-help, New Wave, and “alternative” discourses boomed in Argentina, particularly following the country’s catastrophic 2001 economic and political crisis. Much like the fetishistic journalists suggested, crisis did motivate some to search for a response in psychoanalysis, but the profession itself suffered from the downturn which, as Plotkin and Sergio Visacovsky showed, exposed deep problems within the Argentine psychoanalytic world. In fact, the rhetoric of crisis and disaster pervades Rolón’s writing: Historias de diván opens with a preface that reads: “Every time the phone in my office rings, I know that someone on the other side of the line is asking me for help. And that’s where I find my place as an analyst. In the space someone opens between anguish and pain, between powerlessness and the desire to leave suffering behind” (all translations are my own). Whenever an individual enters crisis—i.e., “every time the phone rings”—Rolón regards himself as their savior, and inflated self-importance veers towards sentimentalism regarding his analytic practice while nuance and the sobriety requisite for such a serious task go by the wayside. In his hands, the psychoanalyst becomes deific, a messianic figure endowed with a Boolean curative power. It’s hard to argue with the vision, since those of us committed to psychoanalysis know its sometimes life-saving power, but Rolón’s self-regard impedes a more realistic or at least reflexive appraisal. Every conversation becomes life or death, health—“leav[ing] suffering behind”—and “anguish…pain…powerlessness.” In this binary, Rolón turns himself into the only possible steward from one to the other, like Kafka’s doorkeeper in his parable “Before the Law.”

Endowed with limitless self-importance, Rolón also worships the patient capable of acting on their “desire to leave suffering behind,” the patient who calls his office, who demands his time. The patient who understands that the path away from suffering is through Rolón, whose work brims with trite glorifications of striving, mainly that of patients but also his own. For Rolón, every patient is Robinson Crusoe in voluntaristic isolation, and his interest lies above all in ennobling “the desire to fight and the bravery of people who chose to go in search of their truth to end [their] suffering.”

Another preface commemorates the book’s 10th anniversary, and discusses Rolón’s childhood home of La Matanza, a now impoverished and hyper-populated suburb of Buenos Aires which, during his youth in the 1960s and 70s, was a working-class factory town. Rolón paints the primal pastoral of incipient individualist capitalist success: “The boy I was, who ran barefoot through La Matanza’s dirt roads, still looks up at me every day in amazement.” He follows with an almost certainly fictional and almost violently cliché interaction with his father: ““What are you thinking about?” my father asked me. My arm extended as I tried to cover the immensity that surrounded me. “Everything that lays ahead.” My old man smiled and asked, “Do you like it?” I nodded. “Well, then go search for it and make it yours.”” Such paternal legitimation for Rolón’s ambition reads like an anti-oedipal fantasy in which the Father authorizes and accepts the Son, offering a priori justification for Rolón’s ambition and success. To Rolón, his position as a renowned psychoanalyst-writer and bestseller is but the product of destiny, pure ambition, and fatherly legitimation. His definition of success is similarly dubious: “After the books came the talks, my participation in Psychoanalysis [sic] conferences, classes at universities in various countries, a television miniseries and even a film.” The absence of patients, to whom he claims to be devoted, or even fellow psychoanalysts among his list of achievements is conspicuous. Though a psychoanalyst would be well-positioned to interrogate such self-aggrandizing mythologies, Rolón’s prefaces excessively, almost suspiciously affirm the legitimacy of his success. In undertaking analysis, Rolón writes that patients are asking him to “join them in a journey as uncertain as it is dangerous: the one that leads towards the deepest and darkest parts of their soul.” Psychotherapy becomes dangerous, unknowable, a mysteriously esoteric practice which he will render crystalline and transparent.

Penworthy patients are bootstrappers, self-sufficiently motivated, “someone who suffers and is, at the same time, willing to struggle to stop doing so,” as that preface reads. A committed patient is central to psychoanalytic psychotherapy, and Rolón places a great deal of emphasis on the establishment of a therapeutic contract with each patient, a step that he mentions in every one of the 10 stories in Historias de diván. His disproportionate concern for the transactional aspects of psychoanalysis suggests a radically individualistic, economistic version of psychoanalysis that glorifies effort in a vacuum, as though incapacitation were not often a symptom or context did not exist. In fact, Rolón has a clear disdain for the human patient, preferring the abstract and generic examples with which he populates every book.

The book’s stories share a set of formal traits: an opening narrative that situates this patient within Rolón’s life as a therapist, usually commending their persistence in getting his even though celebrity makes him inaccessible and over-demanded; a first session in which Rolón is unconvinced that the patient “has what it takes” to be his analysand, and a specific insight or remark that wins him over into establishing an analytic relationship; the actual development of the analysis, with the highlights condensed into a couple sessions in which Rolón offers piercing insight that cuts through the patient’s stone front; and, finally, a leap in time that displays how much better patient is doing, if not cured then almost. Though the ailment at hand in each case varies, none of Rolón’s subjects would reach beyond neuroticism towards a debilitating pathology. United by their dogged pursuit of treatment by Rolón, his patients always want help with typical, somewhat mundane matters: incipient divorces and break-ups, affairs, deaths, dysfunctional sex lives, the typical tragedies of bourgeois life. Though analysis can be hugely helpful in such situations, one wonders whether Rolón excludes more severe and challenging cases because such patients rarely display the “zest” he so verbosely praises.

Rolón’s analysis and narration are similarly capsized by a strange conservatism. He follows every revelation by a female patient with an analysis of what particular inner resource helped her overcome tragedy or suffering, emphasizing yet again his doctrine of psychic entrepreneurship: “I think that her sense of humor, the strength she gets even out of her weaknesses, is what helped her never give up.” He also describes female patients, including a 17-year-old who later died of leukemia, in crassly eroticized terms: “sensual,” “slender,” “beautiful,” “seductive.” His male patients, meanwhile, mostly deal with sexual difficulties that range from the outright criminal—systematically exposing themselves to poor women without consent—to relatively innocuous cases of romantic disinterest and sexual boredom. Severe ailments, and the complexities of life, vanish in the margins between Rolón’s clichés and his non-consensual sexualizations, which reduce women (and really, all patients) to the tautologies of cliché.

Of course, the psychoanalytic patient has been figured as femininized since Freud, if not earlier, and the subject of the “psychoanalytic column” in Argentina’s mass media has been middle-class women since the 1930s. Indeed, mass psychoanalysis in Argentina has always leaned conservatively towards immuring and fortifying gender and family roles. Rolón—ever the faithful inheritor of that tradition—presents himself as an intellectual luminary through a reliance on the top-down dynamics that result from this genderedness. Thus, he offers paragraph-long dissertations on “falling in love”— “Look, when you’re a teenager, you fall in love first…It’s more than enough to see the person walking down the sidewalk. You’ve never spoken, but you already love him…”—or other abstractions. Generic expostulation is grotesquely inappropriate for any analyst, of course, but serves Rolón well in his quest to present himself as a wizened scholar. Female patients become, in Rolón’s hands, opportunities for dehumanizing sexualization and, in that very doing, opportunities to confirm his own stature as a theorist.

The same scene transpired on the black leather couch, in that coldly lit TV studio where we began: mostly women celebrities divulging their tortured love lives, Rolón offering something akin to analysis—all talk, no cure—in exchange for applause. Marsilli-Vargas locates such segments’ appeal in Rolón’s invitation to enter “one of the most ritualized and private spaces: the therapeutic session.” Voyeuristic invitations into the clinic are no novelty, though broadcasting them certainly is. I would never argue against Rolón’s democratizing impulse for psychoanalysis, though I would question his own commitment to the requisite humility. Unlike the great promoters of Argentine psychoanalysis, from Freudiano to Germani, Butelman, Pichon-Rivière, and more, Rolón has often simulated and simplified. Lacking a career outside of the media, since he has aggressively mined his private practice for writing material, he fashioned himself into a star. His writing and public presence have also riddled the most accessible version of psychoanalysis for Spanish-speaking audiences, at least in South America, with conservative stereotypes, shot it through with an individualist gospel of work and progress.

Perhaps little remains of the vision that blossomed in the early 20th century of a new path to well-being, indeed of a new kind of well-being, one that eventually promised to transform the world altogether. Though analysis continues in Buenos Aires, with Lacanianism holding particular influence—Jacques-Alain Miller visits yearly—the project has become humbler, less feverishly political. As this neutral, highly institutionalized and regulated analytic culture appeared, Rolón’s star began to rise, allegedly to promote the “sacred flame” of psychoanalysis. Yet to imagine psychoanalysis as simply a collection of ideas, or even as reducible to the frictionless, empty performance of conversation, is to forget its key hope: an impossible cure, freedom from neurosis and repression. No amount of talk show appearances or shallow, fetishistic books will bring that horizon closer.