Reclaiming the Cut, Refusing the Suture

On Scientia Sexualis

Rosie StocktonInnumerable villains mark the history and the creation of modern theories of sex, gender, and sexuality. There are the slaveholding surgeons of modern gynecology, the racist phrenologists, murderous obstetricians, and misogynist neurologists. There are the transphobic sexologists and an entire army of psychiatrists relying on the pathologizing diagnoses cemented in The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (the DSM). Then, of course, there are the psychoanalysts.

The doctors of sex and gender working since the late 19th century are legitimized by the epistemological and political regimes gathered under what Foucault called “scientia sexualis”: the scientification of sex. According to Foucault, the 19th century marked the height of an epochal shift in regimes of knowledge and truth. In his productively generalizing account, there have been historically “two great procedures for producing the truth of sex”: the pre-19th century ars erotica, in which sex was characterized by erotics and pleasure, and scientia sexualis, the 19th century turn to “extract the truth of sex by classifying experience into normal and pathological, stabilizing subjects by crafting typologies of their desires.” This shift left a modern archive of violence in its wake.

Taking its name from Foucault’s phrase, Scientia Sexualis, on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (October 5, 2024–March 2, 2025), is organized around visual art produced after 1990 that grapples with this archive. The 27 artists in the show, curated by Jennifer Doyle and Jeanne Vaccaro, stage decolonizing interventions into scientific discourse and confront its violent legacy. Names are named, textbooks are cut up and bound, sadistic medical devices are reappropriated for pleasure, diagnoses are mocked, and graves are desecrated.

“Names are named, textbooks are cut up and bound, sadistic medical devices are reappropriated for pleasure, diagnoses are mocked, and graves are desecrated.”

Quite literally. KING COBRA’s (documented as Doreen Lynette Garner) sculpture Fuck Baloney (2023) incorporates dirt from the gravesite of the ‘father of modern gynecology’ and plantation physician J. Marion Sims into layered slices of pink silicon baloney. The sculpture recalls her 2017 piece Purge, in which she cast a life-size statue of Sims in the same pink silicone, later carving it with a deli slicer during a performance as part of her exhibition “White Man on a Pedestal.” In the Scientia Sexualis exhibition catalog, C. Riley Snorton contextualizes Sims’ legacy: between 1844 and 1849, Sims personally enslaved twelve sick women and girls on his farm in Alabama, whose Black bodies non-consensually became the grounds for the supposed advancement of medical gynecological knowledge. As you walk through the show, Cauleen Smith’s banners hang overhead, punctuating the ceiling of the museum as colorful tapestries commemorating the names of Sims’ victims in hand-sewn script—“Lucy,” “Anarcha,” “Betsey.” The banners also declare phrases that invoke the direct address to interpellate viewers into our own generational complicity: ‘YOUR DISCIPLINE UN-DID ME.’ This address casts the viewer as both the disciplinarian and the invitee into discourses of revenge and repair.

Your discipline un-did me (2023), Cauleen Smith

Sims’ legacy is underwritten by colonial regimes of violence, marked by the first piece you encounter when walking into Scientia Sexualis: Demian DinéYazhi’’s mural POZ Since 1492 (2016/2024). Operating like a Sphinxian riddle before Oedipus’ arrival in Thebes, the mural looms over the ICA’s parking lot, depicting a photo negative scene of the myth of European colonizers and American Indigenous people sharing food. DinéYazhi’’s piece asks us to perform an interpretive act before entering the museum: to consider the relation of modern sexual science in the 19th century to a foundational colonial act of genocide, expropriation, and infection. (Like Sylvia Wynter’s reference to the overrepresentation of “Man” in the colonial origins of the Human, we recall here that answer to the riddle of the Sphinx in Oedipus’ tragedy is “Man.”)

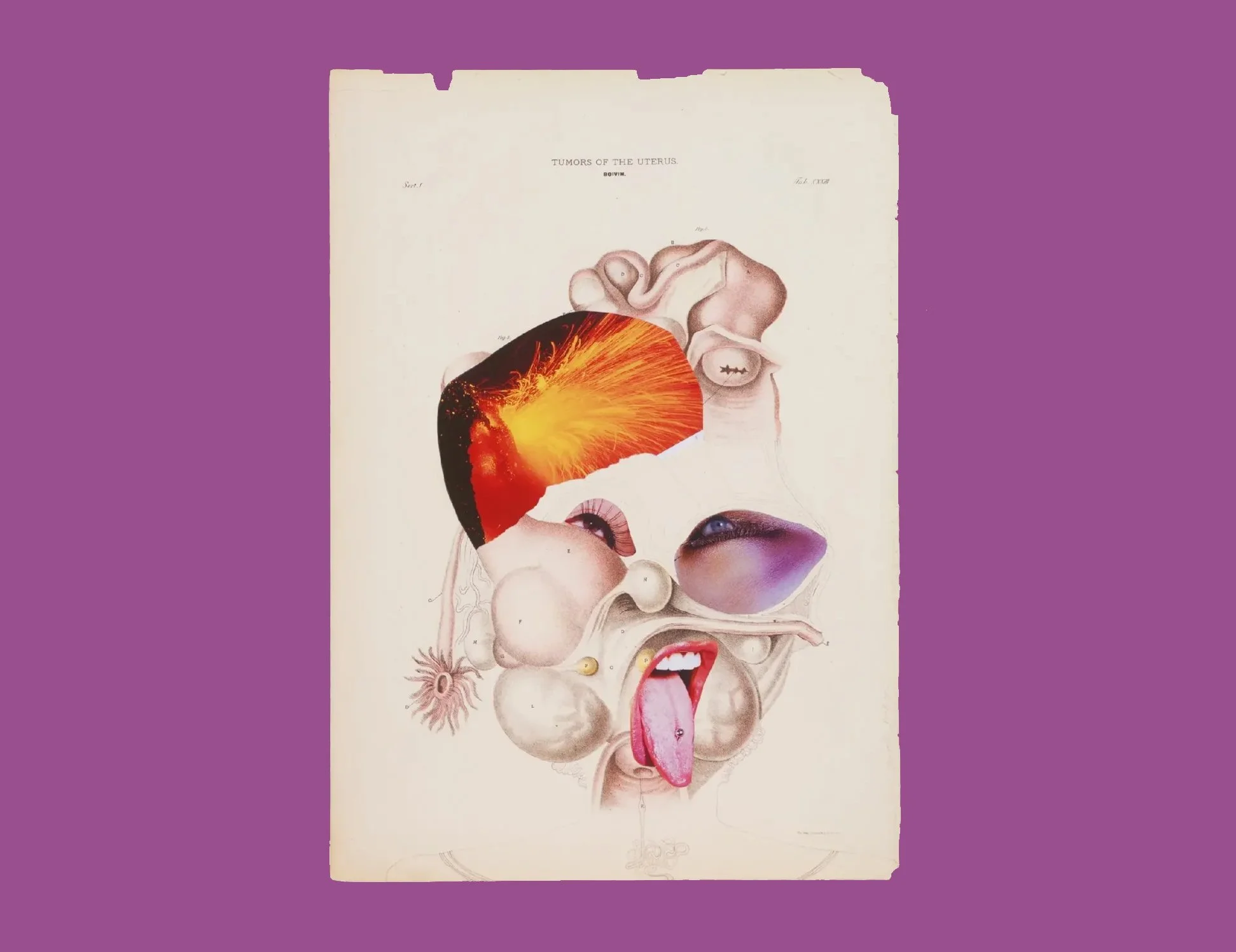

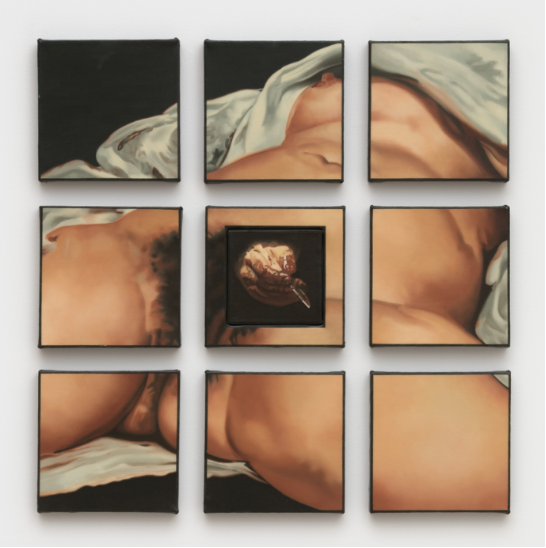

A rolodex of lesser-known figures of the gory history of sexology, gynecology, and medicine are the anti-hero muses of the show, whose legitimacy and legacies of pain the artists on view work to dismantle and avenge. In Histology of the Different Classes of Uterine Tumors, Wangechi Mutu disrupts the medical gaze by cutting up John A. Jeançon’s 1887 medical atlas, Diseases of the Sexual Organs, to create surgical collages that splice genitalia with images of women from beauty, fashion, and porn magazines. Nearby, Candice Lin’s Night Moon (2024) references the textbook The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures (1774) by William Hunter, a Scottish doctor who attempted to legitimize midwifery by experimenting on pregnant women who were likely stalked and murdered. In the center of the gallery stacks of the DSM-IV-TR (the last edition to pathologize “gender identity disorder” as a diagnosis) are bound in shibari knots and occupy a model of a lit up dance floor in Joseph Liatela’s On Being an Idea (the right to live without permission) (2020). On the other side of the gallery, Louise Bourgeois’ bronze Arch of Hysteria (1993) hangs larger than life, frozen in contortion, iterating a hysteric’s posture. The arched woman’s body references Pierre Andre Brouillet’s 1887 painting A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière, which depicts the neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, otherwise known as “the Napoleon of the neuroses,” giving a lecture on the fainted woman on his arm. Around the corner, a bloody dismembered hand of surgeon Dr. Samuel D. Gross is cut out of Thomas Eakins’ 1875 painting The Gross Clinic. It occupies the centerpiece of Dotty Attie’s painting Disturbing Rumors (1994), which features a mathematically cut up and painted grid of Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du monde (1886), invoking the verifiable “rumors” of Eakin’s sexual violence and abuse.

Disturbing Rumors (1994), Dotty Attie

Which brings us to the show’s reckoning with two of psychoanalysis’ notorious Founding Fathers, Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan. In the exhibition catalogue the curators direct our attention to what could be dismissed as petty biographical gossip (perhaps the epistemological mode we can trust in most). First, that Brouillet’s A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière hung in Freud’s office over the analytic couch, where he, like Charcot, treated hysterics not with hypnosis, but with psychoanalysis. Second, that Courbet’s L’Origine du monde was purchased by Lacan in 1955 and was hung at his summer home. It may come as no surprise that Lacan sought to possess a painting called the “origin of the world,” just as it is no surprise that Freud, (in what seems like a bad joke) would have aligned himself with the Napoleon of neurosis.

Scientia Sexualis begs the question, what do we do with the scientific techniques enabled by racist, colonial, and misogynist forms of truth? What concepts and methods can be salvaged from discourses founded on compulsory conceptions of the human and its medical categorizations? Following and invoking a lineage of theorists like Sylvia Wynter and Hortense Spillers, the works in Scientia Sexualis advocate for the sabotage of the regime of truth codified as “scientia sexualis” in favor of a new epistemological regime, or what Sylvia Wynter would call a new “mutation of knowledge.” Taken as a whole, transferential relationships between the works in the Scientia Sexualis provoke such a mutation of the procedures of truth in psychoanalysis.

*

Joan Lubin, in the catalogue essay “Sex by the Book,” links the shift from ars erotica to scientia sexualis to the rise of talk therapy and Freudian psychoanalysis. If under the epistemological regime of ars erotica embodiment had the monopoly on sexual truth, under scientia sexualis, “sex… had to be put into words.” While secularization of truth legitimized itself with “science,” it retained the form of the religious confession. From the confessional booth to the analyst’s couch, psychoanalytic subjects describe “their urges and anxieties to an impassive analyst who distinguishes pathological psychoses from benign Neuroses.” Inaugurated in the late 19th century, the project of psychoanalysis was one haunted by the “truth of sex.”

The show’s ambivalence toward psychoanalysis is perhaps most clearly depicted in Nicole Eisenman’s painting The Session (2008), a “self-portrait” of the artist lying on the couch in the office of her psychiatrist father’s office. The walls are lined with books from the history of psychoanalysis and philosophy, a clock counts down the minutes of the session, African masks appear on the wall, and a dildo-shaped flower case holds a limp daisy. Her nose is comically red and enlarged, throbbing even, evoking Freud’s early and abandoned theory of the naso-genital relationship, influenced by his frenemy Wilhelm Fliess, a surgeon-butcher who Freud allowed to perform a surgery on his sinuses in an attempt to cure his neurosis (and who also severely disfigured a patient that Freud had referred to him in a nasal surgery gone wrong).

“The walls are lined with books from the history of psychoanalysis and philosophy, a clock counts down the minutes of the session, African masks appear on the wall, and a dildo-shaped flower case holds a limp daisy.”

The history of Freudian pathology is also the topic of the immersive two-screen film Schreber is a Woman by the collective El Palomar (R. Marcos Mota and Ama Sánchez), which resurrects German judge Daniel Paul Schreber’s Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (1903), made famous by Freud in The Schreber Case. In The Schreber Case, Freud used what he called Schreber’s psychotic “delusions” of womanhood as the grounds for developing the claim that paranoia is a defense against homosexual desire, particularly for the father. This claim has been subsequently taken up to justify homophobic and transphobic diagnostic methods in both psychoanalysis and psychiatry. Freud has been widely criticized for such speculation, and El Palomar joins in the chorus of criticisms by accepting Schreber on her own terms: as a woman. The split screen parodies binaries, and episodes taken from Schreber’s memoirs are re-enacted with soothing voiceover and electronic music. Unsynchronized twinned scenes of Schreber self-pleasuring are interspersed with her lecturing at the chalkboard, disrupting the interlinked knowledge systems of European imperialism, scientific racism, and the pathologization of gender deviance. Schreber is a Woman depicts Schreber’s illness in terms of pleasure and carves out a space where her “delusions” make perfect sense. It is not Schreber who is mad, it is society.

Schreber is a Woman (2020), El Palomar

The question of gender and sex difference in psychoanalysis has always landed most brutally on trans people. In psychoanalysis’ pursuit of the truth of sex, Lacan updated Freud’s ill-fated declaration that “anatomy is destiny” when it comes to the Oedipal arrangements that initiate sexual difference. Where the anatomical penis was overdetermined in Freud’s formulation, in Lacan’s schema of sexuation the phallus is the organizing principle indicating a discursive lack initiated by the subject entering into language. That is, one is retroactively sexuated in the feminine position or masculine position depending on one’s position in relation to the lack the phallus stands in for. No one “has” the phallus: each subject, no matter their sexuation, is “castrated” in the face of language. Despite contemporary Lacanians’ complicity in the pathologization of transness, many have argued this theoretical shift offers potential for disrupting essentialist notions of gender. Lacanian Patricia Gherovici argues that to be “gendered at birth” is a mistaken aligning of the phallus and the organ. The trans subject’s “demand for a sex change” therefore is not a psychotic attempt to overcome sexuation, or lack itself, but “is meant to rectify this error in the Symbolic register by correcting the error in the real of the body.” In the ICA show, Jen Fan’s sculpture Form Begets Function (2020) stages such an intervention by reclaiming the materials from their raced and sexed identity categories. Made of urine, melanin, and Depo-Testosterone contained in melting, formless glass globules, Fan delinks the materials of the body from their hegemonic gendered associations.

*

Psychoanalysis has been criticized not only for being homophobic and transphobic, but also for being predicated on a fundamental humanism coherent only via the logics of anti-Blackness. In Scientia Sexualis’ pursuit of unraveling the truth of sex, many of the works are in conversation with critiques of the racialized origins of the category of “the Human,” and race is centered as an enabling structure of sexual difference. Hortense Spillers has argued that Freud’s universal human subject and normative Oedipal kinship structure is modeled on the white European family. She writes that the occluded “race matrix” was “the enabling discourse of founding psychoanalytic theory and practice itself” and that “the universal sound of psychoanalysis… must be invigilated as its limit.” Echoed by many scholars like David Marriott and Sheldon George, race is situated as the original difference undergirding the structure of sexuation. Lacan’s famous assertion of negativity—“woman does not exist”—misses a deeper ontological form of difference.

The question remains: can psychoanalysis undo the Gordian knot of questions regarding the anti-Black organization of sexual difference in its contributions to the history of sex, sexuality, and gender? To answer this question I turn toward what is latent in Scientia Sexualis: the transferential relationship between P. Staff’s Depollute (2018) and KING COBRA’s Vesico Vaginal Fistula (2016), where the unconscious of the exhibition beautifully bubbles up, marking the dual crises of race and transness unaccounted for in the normative neurotic subject of psychoanalysis and its attendant crisis of sexuation.

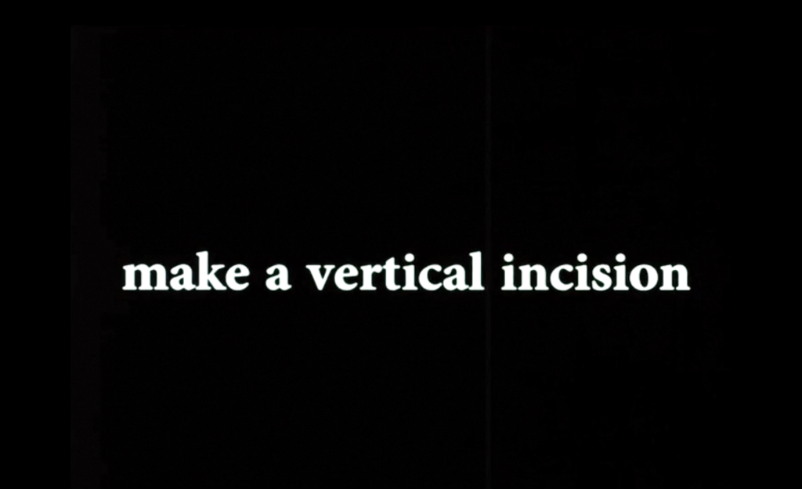

During a tour led by curators Jeanne and Jennifer, we lingered at P. Staff’s Depollute (2018), a two-minute video that strobes with pared down text instructing the viewer how to perform a self-orchiectomy. While watching the film, Jennifer turned toward the adjacent sculpture, KING COBRA’s Vesico Vaginal Fistula (2016), and noticed—with surprise—that the flickering words of Depollute could be seen reflected in the mirrored encasement of the neighboring piece.

On the right, Staff’s Depollute includes wall text that you must request museum staff to turn on the video piece, indicating your desire to see it. “Part instruction, part poetry,” technical surgical words flash across the screen, immediately derailing the viewer’s fantasy that she might see footage of self-orchiectomy described in the wall text. This thwarted desire becomes the material of the piece. As Eva Hayward argues in her catalogue essay “Light Cut Sex,” this desire is to consume an abstraction of transness, particularly transfemininity, as sex itself. The brilliance in Staff’s piece emerges both by betraying the desire inherent in Freud’s castration anxiety and by complicating Lacan’s formulation of symbolic castration—the process by which the subject enters into language. The instructions in Depollute cut both into the Real of the body and the symbolic order that initiated the already castrated subject. Refusing terms of sex and gender, the flickering text of Depollute produces a queasiness in the viewer, not only because of the strobing images, but also, as Hayward argues, “because the spectator wants to see (the transsexual as sex) and not because of what is seen. After all, perhaps what is most abject to us is our own desire; even more so, its orientation toward violence.”

To the left of Depollute, KING COBRA’s Vesico Vaginal Fistula (2016) consists of a mirrored case holding a visceral sculpture of raggedly stitched reproductive organs made with silicone and hair weave. Vesico Vaginal Fistula references the surgery that Sims developed in 1845 by non-consensually using the bodies of enslaved black women, turning what Spillers calls “captive flesh” into a “living laboratory,” to perform experimental and unanesthetized gynecological surgeries to treat vesicovaginal fistula, an injury resulting from difficult childbirth. As Snorton argues in the exhibition catalogue, VVF functions historically as “a sign of slavery.”

Vesico Vaginal Fistula (2023), KING COBRA (documented as Doreen Lynette Garner)

KING COBRA’s Vesico Vaginal Fistula commemorates the legacy of anti-Black violence encapsulated by surgery performed on captive flesh, asking the viewers to behold our own face in the mirror while confronting a literalization of Spillers’ “divided” and “ungendered” flesh. Dehumanized and ejected from normative conscriptions of womanhood, Spillers argues the black woman as flesh enables the symbolic order and its dominant grammar. The mutilated Black flesh on display is in service of guaranteeing the enslaved women’s future potential to reproduce future chattel, following the logic of the 1660s legal doctrine: Partus sequitur ventrem. That is, Sims’ surgeries were first performed in service of the reproduction of (Black) kinlessness, marking a tear in the fantasy of the white Oedipal family. If, for Gustave Courbet, the white woman’s vulva is the “origin” of the “world,” for KING COBRA the origin of the world is instead obscured from view, symbolized and embodied in the black female mutilated reproductive organ. But we may alter the signifier “world” to center Black maternity as the origin, rather, of life. After all, following Denise Ferreira da Silva, any Black Feminist project must be in service of the End of the World. KING COBRA’s Vesico Vaginal Fistula is a world-ending piece.

In a dizzying moment of transference between the two pieces, the “orientation toward violence” in Staff’s piece is reflected in the mirrors of KING COBRA’s. While Staff’s Depollute refuses the spectacle of transsexuality with the material of flickering language, KING COBRA’s Vesico Vaginal Fistula demands the viewer witness the violence of “pornotroping,” what Amber Jamilla Musser describes as “a process of objectification that violently reduces people into commodities while simultaneously rendering them sexually available.” In the reflection, the divided Black flesh becomes the mirror(ed) stage—the entrance into the symbolic—the very grounds upon which subjectivity coheres. In this case the subject reflected is (white) transfeminity, whose cut flesh works in service of claiming a gendered position. The instructions for the self-orchi surgery are reflected in the VVF surgery: captive black femaleness becomes the condition of possibility for white transgender subjectivity to cohere. At the same time, the methodology of reclaiming the medical agency depicted in Depollute is cast onto the surface of VVF. While self-surgery may not be the utopian vision of gender-affirming care, its flickering instructions signal a breaking with signs of sex and a longing for a symbolic—and political—order where gender becomes more livable. In both pieces, a refusal of the categorizations of sex and gender culminate. Our vocabulary of repair is inverted: one organ is brutally sutured in the name of captive life, the other’s cut up organ is in the name of autonomy and self-determination.

Still from Depollute (2018), P. Staff

The transference between two subjects ejected from the normative scriptures of womanhood demands we ask a Spillersian grammatical question: what do the mutilated genitalia of the black enslaved woman have to do with those of the contemporary, free white trans person? The reflection of Staff’s piece in KING COBRA’s does not simply imply that anti-Black gendered violence is the grounds upon or method from which white trans self-determination finds itself. Rather, the transference materializes Snorton’s intervention in trans discourses, that “captive flesh” figures a critical genealogy for modern transness. Snorton proposes that blackness and transness overlap in their referentiality “inasmuch as blackness is a condition of possibility for the modern world and insofar as blackness articulates the paradox of nonbeing.” Snorton uses the concept of “transitivity”—a theory both of change with no particular arrival and a reference to an “expression of an action that requires a direct object to complete its sense of meaning”—to replace dominant notions of transitioning. Following Snorton’s argument that blackness and transness are in transitive relation both as a grammatical and a social fact, we may reformulate the relationship between the pieces as transitive rather than transferential. In psychoanalysis, transference refers to the analysand’s projection onto the analyst as the subject-supposed-to-know. Staff’s and KING COBRA’s pieces explode this notion of transference between two subjects into a more constellatory, transversal form that insists on breaking up the ontological grounds of gendered being. The curators’ conscious coupling and proximity of Staff and KING COBRA’s work produced an unconscious consequence: their transitive relation with each other.

“As Scientia Sexualis insists, this structural antagonism where Blackness and transness refract is precisely where a politics of solidarity must emerge.”

As Scientia Sexualis insists, this structural antagonism where Blackness and transness refract is precisely where a politics of solidarity must emerge. I write this on the day Trump put out the federal aid funding freeze memo that states “The use of Federal resources to advance Marxist equity, transgenderism, and green new deal social engineering policies is a waste of taxpayer dollars that does not improve the day-to-day lives of those we serve.” As Trump attempts to ban DEI, trans healthcare for children, and mandates the elimination of pronouns from CDC websites, Scientia Sexualis urgently asks us to consider how questions of sex and gender are intertwined with fascist policies regarding borders, citizenship, and class. At the heart of these intersecting logics of oppression are the necropolitical orders around who counts as human, whose life is worthy of protection, and whose isn’t. As Sylvia Wynter puts it, the colonial and racial origins of the category of the Human is overrepresented by “Man” rooted in Western liberal conceptions of humanity that require a racialized nonhuman “other.” The trans panic and racism of the fascist right is a result of intertwined logics of sex and race that consolidate in the borders of the Human. This formation of the Human is one that enables the legitimization of racial capitalism and authoritarian state orders. This same Human occupies the broken center of psychoanalytic discourse.

*

What would psychoanalysis be with a mutated conception of ‘the Human’? Vaccaro and Doyle write in the exhibition catalogue that “the artwork in this exhibition is a form of medicine, an attempt to address and cure sites of injury.” Psychoanalysis, famously, evades the idea of the cure. Instead, Freud has claimed the goal of psychoanalysis is to transform unlivable “neurotic misery” into “ordinary unhappiness.” The works in Scientia Sexualis are not content with ordinary unhappiness. Refusing the non-consensual suture of modern science and taking the cut back from the analyst, Scientia Sexualis dispossesses the big Other from its monopoly on sexual knowledge and reasserts bodily and psychic autonomy. The show ends the world of the modern regime of knowledge encapsulated in ‘scientia sexualis’ in favor of an epistemological mutation. Moving beyond both Freud’s anatomy and Lacan’s negativity, the show proposes a sexual politics that reclaims madness and pathologization, and disrupts racialized ontologies of the human. It leaves us to consider, if psychoanalysis was enabled by the epistemological shift from ars erotica to scientia sexualis, what might the next regime of truth be called?