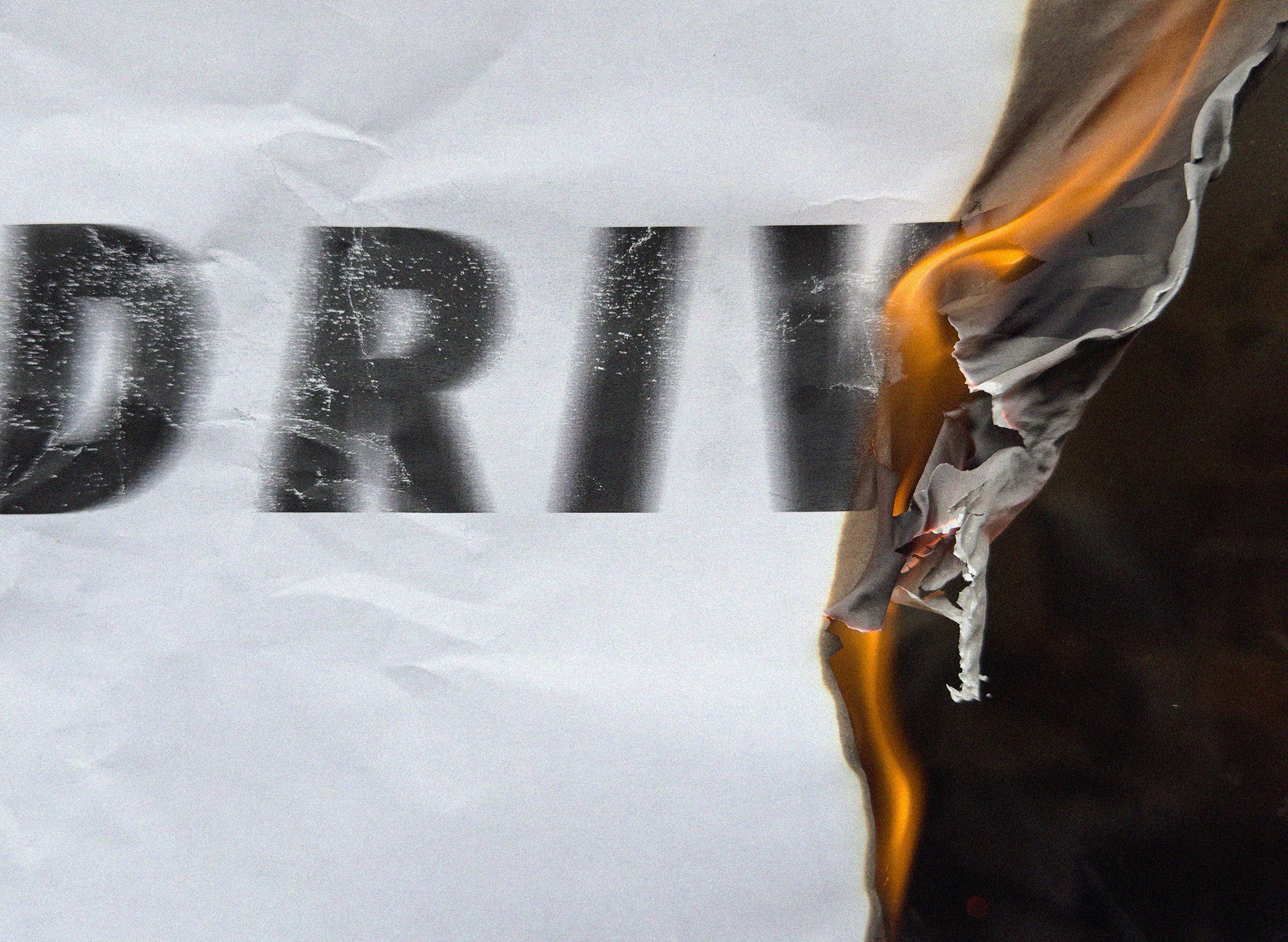

We Didn’t Start the Fire

Death drive against ecocide

Anna KornbluhIt is too late.

July 2023 set the record for the planet’s hottest month in possibly 120,000 years. Heat death, catastrophic droughts, and lethal deluges are baked into the immediate future, no matter what action is taken today, because of choices in the past. In 1992, the first United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change had already compiled enough terrifying data to compel virtually every country on earth to recognize the severity of climate change, commit to mitigating greenhouse gases, and do so in accordance with a principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities.” It has been over for thirty years. Causes have been known. Effects have been known.

Knowledge evidently does not suffice. Confronting that deficit, academics, artists, and activists in this century have roundly embraced “alternative epistemologies” and “imagining otherwise.” But multiplying the ways of knowing has also not transmuted into action; we know what to do but we do not do it. So now arises an abundance of explanation about why it keeps on not being done. On this beat, psychoanalysis is very much in the news. In recent years, it has become compulsory for journalists, clinicians, and theorists chronicling climate inaction to evoke the most speculative of all psychoanalytic concepts: the death drive.

“The living world is being destroyed by dead capital. This is the death drive of capital. Capitalism is ruled by a necrophilia that turns living beings into lifeless things.”

—Dr. Byung-Chul Han, philosopher

“Climate denialism, like COVID denialism . . . [is] the death drive at its most lethal.”

—Dr. Emily Apter, professor of comparative literature

“The planet is what unconditionally matters, since it is the undercommon ground of all life…It’s all dying . . . fire and tempest, signal of internal danger that one might call the death drive.”

—Dr. Richard Seymour, sociologist

“I had used Freud’s theories about anxiety and the death drive as a way of understanding why humans seem unable to move forward together to mitigate their drastic negative impact on the planet . . . [and] how humans got to be a suicidal species.”

—Dr. E. Ann Kaplan, professor of film

“Globalization is a theo-thanato-carboeconomy in which all the spectres of the religious and the political, old and new, circulate in a death drive towards depletion and extinction.”

—Dr. Martin McQuillan, professor of literary theory

“Whereas a previous iteration of queer negativity figured the death drive through an atomistic politics of individual refusal, the intensification of queerness within toxic environments makes unwitting sinthomosexuals of us all. Edelman’s “fuck Annie” has become a collective planetary emission.”

—Dr. Steven Swarbrick and Dr. Jean Thomas Tremblay, professors of English

“The Death Drive is Alive and Well . . . One of the most serious reflections of the Death Drive is the rapid destruction of the planet Earth itself, evidenced by climate change.”

—Dr. David Jachim, psychoanalyst

“The little organism of the death drive explains a lot. We are late capitalist humans in the center of a gerontocratic petrocracy, driving around in cars fueled by the liquid remains of previous mass extinctions; in so doing, we are crashing into one another, dying really quickly, boiling the world, and producing the next great extinction. There is a tragic drama and a legibility to what you could call a thanatotelic trajectory: i.e., a driven-ness toward death in the way in which the nonnegotiability of our comfort and the desire to maintain a nostalgic past produces not just death in the present but increasingly commits us to a self-destruction that’s also a destruction of the other.”

—Dr. Patrick Blanchfield, philosopher

“So much of what rules everything around us—that is to say: cash—incentivizes the further extraction of fossil fuels in spite of the science that explicitly demonstrates that this is little more than a profit-motivated death drive.”

—Prem Thakker, journalist

“Following this death drive . . . salt flats are being sacrificed to extract a non-renewable resource that is at the centre of a ‘green’ revolution.”

—Dr. Camila Vegara, law fellow

“The death drive—as it manifests in normative subjects in the contemporary West—has generated destruction on a macro scale in the form of global climate change.”

—Dr. Robinson Murphy, professor of environmental studies

“A death drive. This country has a death drive. Democrats, Republicans, they are driving the country over a cliff of poverty/COVID/climate with their foot on the pedal, just flooring it for our collective destruction.”

—Dr. Steven Thrasher, professor of journalism

For a radically interdisciplinary and interprofessional consensus—psychoanalysts and philosophers, sociologists and cultural critics, journalists and lawyers—the signifier “death drive” ferries a compulsively repeatable explanation of climate catastrophe. Why are we forcing extinction? Because, according to both lay analysis and high theory, meme-able headlines and academic symposia, there is so much enjoyment in the unholy convergence of best-practice aggression and the growth imperative of extractive capitalism.

The death drive is not a program

Speaking of enjoyment, the very repeatability of this explanation suggests that its satisfactions are manifold. It is of course essential to make sense of the senselessness around us. Yet the sense here is a little too enjoyable. Like all psychologisms, it furnishes the abject succor of exoneration: we simply cannot help it, it is our nature to annihilate nature. In the face of the oft-extolled sublimity of climate crisis—its scale and severity, its complexity and uncognizability—death drive as cause domesticates and rationalizes: this is why we do it. And up against the speculative, inconsistent strangeness of the death drive, this prevailing mantra magnetically assures: drive means. Positivized aggression in the final solution of heat-seeking destruction. Downright irresistible.

To cut to the chase: this ubiquitous warming nugget of contemporary discourse commits theoretical malpractice. Psychoanalysis is understandably resurgent in the quivering void of explanations for rampant immiseration, but the popular front should not misframe its fundamental concepts. The death drive is a theoretical construct, Freud steadfastly insisted, a “limit concept” at the limit of conceptuality, figuring limits to thinkability and consciousness, corporeal borders, and the divide of nature/culture; its liminality and speculativeness court misuse, especially the misuse of taming its wild. One such subdual is this tony settling of the death drive as cause. Taking the death drive as a cause of the climate catastrophe is wrong about causality, both politically and libidinally. Mass psychology is not responsible for carbon modernity’s devastations. And the death drive is not a program.

*

There are therefore two corrections to make, the first political and the second psychoanalytic. Not corrections for correction’s own sake, for schoolmarm rectitude, but to percuss the gratifications of this double mistake. So, OK, schoolmarm kinkshaming. It is evidently enjoyable to believe that humanity is killing itself on purpose. It offers the consolation of our competence, exculpations of our inaction, and ultimately the reassurance that enjoyment is efficient, that drive is in the last instance not a disturbance in the order of being, but efficient manifest destiny. We should question this enjoyment, and as partisans of a renaissance of psychoanalysis, we have a responsibility to traverse it.

On the political point, we can say quite simply that the masses of people—especially those who are already dying, but up to and including those who, on average, suffer only #firstworldproblems—are not responsible for carbon modernity, and to suggest that they are is an egregious obfuscation that debilitates mass mobilization. Carbon capitalist autocracy, a highly specific and contingent mode of resource management and power monopoly, is the cause. Many historians and geologists deem the post-1950 intensification of the human imprint on the earth system of physical, chemical, biological, and human processes “the great acceleration.” This acceleration tracks closely with the dramatic decline in top income tax rates and statutory corporate tax rates globally. It also tracks with the oil companies’ own scientific conclusiveness about anthropogenic climate change. They know it, and they are doing it. The average billionaire emits one million times more carbon than the average person living in the bottom 90 percent; this is not only lifestyles of private jets and yachts and eight houses, but also the aggregate emissions of their investments—in the mere one hundred companies that have been responsible for more than 70 percent of global emissions over the last fifty years. The average fossil-fuel executive is not ignorant of the lethal impact of their actions, but hews to the rational calculus that if they do not profit, someone else will. And these colossal untaxed emitters and wanton oligarchs have in the same timeframe consolidated outsize influence over politics, media, and the rule of law. Political leaders cannot champion drawdown, public infrastructure, or corporate accountability when they are themselves owned by the oil industry; journalists cannot represent the truth when they have been downsized, outsourced, and automated; courts cannot adjudicate rights and freedoms, injury and remedy, when they are only corrupt kangaroos.

These clear causes mean there are some clear solutions. Don’t believe the “it’s complicated” mantra of Latourian ecocriticism, because it’s simple: cutting the carbon footprint of the world’s wealthiest people is the fastest way to reach net zero. No more Exxon Mobil and BP, no more billionaires, no more private planes, no more private senators, no more oil; yes more taxation, yes more pipeline sabotage, yes more lowlands mutual aid, yes more federalized decarbonization and centralized resource redistribution. Yes, this simplicity falls short of communist revolution. But it would ameliorate vast suffering in the looming present. Psychologizing ecocide rules out even those modest remedies.

*

Psychologizing the death drive, for its part, is an error perhaps invited by the rends of ambiguity in Freud’s speculations, or the lurching rhythm of all his efforts to inscribe it, including its maladroit name. Alas, that the drive is not a program has not stopped proper psychoanalytic clinicians and theorists—among them Freud’s own students—from turning it into one. Many have smoothed the lurches in drive theory by empiricizing it, grounding the abstract category in content: aggressive symptoms (negative therapeutic reactions, violent thoughts and acts, death wishes) or even more generic expressions like affects of hatred, envy, or spite. While Freud himself at times made recourse to the odd behavioral example or destructive wish, his fundamentally speculative theory defies those runaway thematizations. When violent phenomena demand explanation, it is only remotely from the clinical context and rank with ideology that the drive answers.

Death drive as explanation for ecocide logically must be levied in general terms: humanity is the virus, we are destroying the planet—and if it comes to the world without us, then nature is healing. In his prominent essay “Death Drive Nation,” Blanchfield parries this false generality with another one by excepting “America” from humanity. American pandemic attitudes, he argues, distinctively offer “an object lesson and exercise in the death drive”: “the death drive is visible in aggressiveness, in physical violence, self-destruction, and self-sabotage . . . the terrain of the death drive is about severing ties, breaking things to pieces, and even suicide . . . a nation founded on a continent decimated by settler plagues, cleansed by genocidal war, and fructified by chattel labor unsurprisingly . . . [operates] a starkly differential calculi of exposure to premature death, workplace risk, and general immiseration . . . this is the logic of the death drive, distilled and accelerated, to which we cling all the way to the very bitterest of ends.” The original sin rhetoric abundant in so many contemporary approaches to American history is here gilded with a teleologizing of psychic life. This country wishes for death, the heart wants what it wants.

But the workings of the unconscious are not quite that orderly, and even Amerikkka is a tale of two cities in carbon form. The pleasures of painting “America” tout court as aggressive plague outweigh the basic fact that we didn’t start the fire—and it is grossly exculpatory to incant that we did. America is not homogenous economically, ideologically, or even libidinally. It is filled with people who struggle tirelessly against autocracy, or who abide poverty similar (by major wellbeing indicators like life expectancy, infant mortality, and risk of homicide) to countries with a tiny fraction of the U.S.’s per-capita economic output—or who do both at the same time and have for generations. Where America is exceptional is as the world’s largest oil producer and simultaneously the least representative of democracies; purposely and functionally antidemocratic institutions like the Electoral College, localized election laws, the Supreme Court, dysregulated campaign finance, criminalized protest, and militarized policing cow those struggles.

In the pretense of facing a bedrock psychic truth, the pervasive death drive thesis operates as a defense against the real: a dissimulation of class antagonism. And embedded in this political error lurks a psychoanalytic error, a misprision of drive. If the ideological distortion in this death drive thesis vindicatingly grafts the particular ecocidal social class onto the universal subject of the drive, the libidinal distortion gratifyingly represses the fact that the drive itself cannot operate as a cause. The pervasive theoretical malpractice of psychologizing ecocide as purposive drive accords new swank to psychoanalysis, but that comes at the price of illuminative interpretative power.

The pleasures of painting “America” tout court as aggressive plague outweigh the basic fact that we didn’t start the fire—and it is grossly exculpatory to incant that we did

For its proponents, as we have seen, drive is the effective curriculum of destruction. But in psychoanalysis, it is something else entirely. Right away, at the very beginning, the death drive emerges in Freud’s thought as this something else: as he contemplates the mass death event of World War I, the question that propels him as an already established inventor of a new science is not “‘What caused this great violence’ but ‘How does traumatic loss constitute the subject?’” In Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud finds a psychic inclination not for death, but against it—a repression of mortality, a fantasy of heroism, a will to revisit trauma in order to sublate it, a wish not to die. Shell-shocked veterans, with their recurrent symptoms, present not wish fulfillment but the lack of wish, a void where desire magnetically stirs without object. For a different sort of thinker, the Great War context might readily have inspired the psychologism we have seen in the contemporary ecocidal death thesis, but Freud stood vigilant against psychologisms. Where there is widespread insistence that we wish for our own death, there is surely repression. And repression, the non-reckoning with the gap in being and the discontent in culture, is the starting point for psychoanalytic intervention, not its outcome.

Of course that reckoning is enormous, catapulting the science of psychoanalysis toward its most speculative domains. Thus did Freud avow in “Anxiety and Instinctual Life” that “the theory of the drives is, so to speak, our mythology. The drives are mythical entities, magnificent in their indefiniteness.” The very signifier “drive” marks the magnetism of what is unspecified, the undertow of the unknown. Can the practice in the clinic broach or tether the abstract cosmos that is its subject? Mythology is in the room with us—the necessary fabulation of the unconscious. Drive theory is the metafabulation, sketching the kinesis of the indefiniteness. In this the theory reflects its object, for, in the words of Tracy McNulty, “the ungivenness of the death drive” engenders “the corresponding need to substantiate or construct it.” Drive is not a positivity.

Such not-ness—drive’s negativity as it were—constrains it from materializing as the unarrested progress of annihilation imagined by the compulsive consensus on ecocide. Paradoxically, the movement of the negative also constrains the drive from absolutist negativity of the sort promulgated by celebrated antidialectical accounts of the drive. Supposing drive as “antisocial,” a “radical refusal of meaning,” a pure “emptiness” devoid of temporality, Lee Edelman’s conceit founds the theoretical malpractice in our present, for to posit drive as “the unintelligible’s unintelligibility” requires repressing that the negative cannot self-identically engorge. Drive is constantly at odds with itself, a movement of non-immanence that defies instantiation, including instantiation as absolute defiance, in one direction.

Through this dynamic rather than static negativity, drive circles around but does not willfully pursue an object. Freud underscores this generative detour in figuring drive not as line but as short circuit: Kurzschluss, an aperture and excess. To the drive, the object “is strictly speaking of no importance. It is a matter of total indifference,” as Lacan, quoting Freud, defines. Radically objectless, drive is not bullet-journal attainment of a wish. On the contrary, drive is goal-obstructed or zielgehemmt—variable, contingent, and evincible only in its vicissitudes. If there is a wish to return to a prior state of inanimacy, we are pretty bad at fulfilling that wish. What is drive but the topology of failing that return? What is life but the accumulation of the failure to die? The death drive ecocide thesis represses all this failure, obstruction, indirection—all this life—and takes pleasure in a fantasized facility of the unconscious behind an imagined immutability of climate calamity.

Drive is not a program, not a successful enterprise of rationalized destruction, not death brought to you Just in Time by Fulfilment Services, Inc. Beyond the principle of pleasure, the death drive cannot be synonymized to the manifest pleasure taken in perpetrating climate disaster by hoarding power. Drive harkens not economical death but excessive undeadness, what Lacan calls “indestructible life.” Excess exudes: objectless, irrational, electric, free. And it adumbrates a politics of drive through which construction eclipses destruction.

The creativity of the drive has long been elemental to psychoanalytic theory and should not be drowned out by the surging deluge of wish-fulfillment death drive theses. To Freud, in important affinity with Marx, drive is “the demand made upon the mind for work/Arbeitsanforderung.” In us more than us, the stirring to work marks the human beyond animal, the disturbance in the realm of organicity that transforms and terraforms, crafting a metabolic rift, an irreducible generativity. Lacan foundationally declares the creativity of this work: the death drive is “the will to create from zero, to begin again . . . to make a fresh start.” Such creativity animates the theory itself; as Lacan surmises, “the drive, as it is constructed by Freud on the basis of the experience of the unconscious, prohibits psychologizing thought,” and in the place of that psychologism, he affirms artistic composition: “the concept of the drive represents the drive as a montage.” Through assembly and tessellation, drive creates, and just as art indirects and surprises, drive takes the byway; Joan Copjec observes that “sublimation is not something that happens to the drive under special circumstances; it is the proper destiny of the drive.” What happens is precisely not repression, but an evasion of that fate, a looping and surging. Drive’s circuits and dodges, feints and recursions link it profoundly to sublimation’s prime manifestation, art.

Propulsive, galvanizing, drive creates arts and acts, divagations and mediations, through its failure of goal and its inefficient inertia. “The drive persists,” the dearly departed Mari Ruti writes, in “the bourgeoning of creativity . . . [leading] beyond survival to something more life affirming.” Just as misdirection is its name, the death drive obtains at the level of life. Here would be the legitimate generality of drive: not that everyone on planet earth is united in destroying our habitat, but that the disquiet of being compels us beyond hitherto existing civilization, toward freer constructions. Instead of a docket of destruction, drive is better thought—dialectically thought—as this velocity of creation. That we keep on not dying, that we keep failing to attain any specific goal, that we tarry and make and create.

This generative topos of drive motivates psychoanalytic theory’s perpetual recurrence to questions of art, construction, and freedom. “The organism wishes to die only in its own fashion” (nur auf seine Weise sterben will), Freud composes; the fashionable flair of means is determinative, not the end. Such emphasis on medium and mediation marks one of the many lines in the sand between psychoanalysis and the trendy nihilisms of so much contemporary antitheory (dematerialized, ontologized pessimism and immutability). The conceptual dereliction of explaining climate catastrophe as death drive repudiates this line, and thus forecloses a genuine politics of drive.

Insisting on this line against the present consensus stakes the possibility of generative solidarity and divertive acts, a politics of drive that poses quite an alternative to necrotic hoarding by lossless overlords. Drive politics portend not the teleological wish for ecocide, but the crafty deviation from the end. What Todd McGowan posits as “the embrace of repetition” and Molly Anne Rothenberg specifies as “emancipation from the given” can align toward mitigation: keeping life keeping on, in new cul-de-sacs, through secondary satisfactions, institutional workarounds, and aleatory indirections. It is too late, but things can still be less worse. For those interventions, those moderating interpositions and middling intercessions, there is no greater renewable resource than the velocity of the drive, its satisfying failures, its work beyond inertia, its negation of negativity, its intrinsic mediations.